Over the weekend, a friend showed me her wallet full of carefully labelled credit cards. One card was labelled “gas”, another “rental cars”, and another “grocery”. She had applied these labels to remind her which card to use where. That was all great. Then I saw one card was labelled simply “2.73”. I asked what that was about. She answered that it was her Freedom Unlimited card using “your numbers”. She meant that the Freedom Unlimited card earns 1.5X everywhere, so with the Frequent Miler Reasonable Redemption Value (RRV) for Chase points at 1.82 (at the time), the Freedom Unlimited earns 1.5 x 1.82 = 2.73%.

The RRV problem

My friend was using the Reasonable Redemption Values (RRVs) not as intended. RRVs estimate how much travel you can reasonably expect to get from your points if you use those points wisely. I think that’s useful when trying to decide which points to use for an award. Will you get more value than the RRV? If so, you can call it a win. Similarly, I find RRVs useful for comparing credit card welcome bonuses. We use RRVs to estimate “first year value”. The idea is to be able to compare, across cards, how much travel value you might get from the first year of owning the card.

RRVs were not meant to tell you a good price to buy points. In fact, you should never buy points for the same price that you’ll redeem them for. You should always look to buy them for less. Here’s an example: suppose you can buy a flight to Europe straight-up for $1,000. And further suppose that it would cost $1,000 to buy enough points to book that same flight as an award. Would you buy the points? No, of course not. The only reason to go through the extra hassle of acquiring points is if you’ll either save money or get a better outcome such as first class instead of coach.

When you decide to use a points earning card over a cash back card, you are essentially buying points. Here’s an example: if you can choose between earning 2% cash back or earning 1.5 Chase Ultimate Rewards points per dollar, then picking Chase points costs you 2 cents for every 1.5 points you “buy”. In other words, by making that trade-off, you are buying Chase points for 1.33 cents each. Nick covered this topic in detail in his post: How much do you pay for your miles and points? And, I’d argue that 1.33 cents is a fair price to pay for Ultimate Rewards points, so that’s fine. The problem is that my friend was using the 1.82 RRV number to decide which card she should use. By labeling her Freedom Unlimited as “2.73%”, she would likely use this card instead of a card earning 2.5% cash back (if she had the Alliant card, for example). If she made that choice, she would be essentially buying Chase points for 2.5/1.5 = 1.67 cents per point. That’s not terrible, but it’s also far from a bargain, especially if she uses those Chase points to buy travel through Chase Travel℠ for 1.5 cents per point value.

RRVs were not intended to be used for comparing credit card spend rewards. As I mentioned earlier in this post, I think that RRVs are a decent way to compare credit card welcome bonuses, but that’s because credit card welcome bonuses do not have the same type of opportunity cost as points earned through spend. There are opportunity costs involved in signing up for new cards, but they’re different in nature. That topic could easily make for an entire post or two. With points earned through spend (or from shopping portals for that matter), there are clear cash trade-offs which make it important to consider the opportunity cost of earning points rather than cash. If my friend doesn’t have any cash back cards to compare to, then RRVs are a fine way to compare the relative value of credit card rewards. But when cash rewards are part of the equation, I think a better metric would be an estimated cash value, rather than estimated redemption value. View from the Wing describes this concept as “the amount at which you are indifferent to holding miles versus cash.”

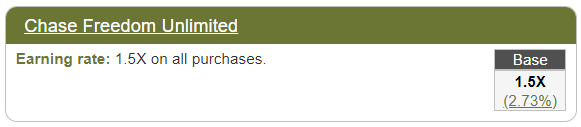

It’s my fault. Not long ago, I enhanced our credit card displays to show point earnings in the form of RRVs. For example, the page “Best Everywhere Else Rewards Cards,” previously showed this for the Freedom Unlimited:

See how it says that the Base earnings for this card are 1.5X which equals 2.73%? Yeah, that’s my bad. That display absolutely encourages the RRVs to be used the way my friend was using them.

Identifying the correct cash value is an impossible task. I described this problem at length in the 2013 post “Impossible point valuations and the joy of free.” There I discussed the fact that points are worth more or less based on how they’re used, how many you already have, how easy they are to use, whether or not they add value (such as free flight changes), whether or not you have elite status, your travel habits (e.g. airline miles are often worth much more on international premium cabin flights), and your subjective value of the “joy of free.”

It is important for us to establish estimates, even though getting it right is impossible. Most consumers have no idea how to estimate the value of points earned. For example, many consumers would assume that Hilton cards, which earn at least 3 points per dollar on all spend, must be better than the World of Hyatt card which earns only 1 point per dollar for most spend. In reality, most of us who understand the relative value of these points would probably choose 1 Hyatt point over 3 Hilton points (unless you frequently use Hilton points at category 1 and 2 hotels) if we didn’t have a brand preference. In other words, I strongly believe that consumers need some guidance as to how to value points and miles.

A better solution may be to estimate ranges based on use case scenarios. For example, “for those who use points to fly domestic economy, United miles are worth between XX and YY.” Ranges would be more accurate, but less useful. Ultimately our goal is to compare rewards earned from different cards, different promotions, different portals, etc. Point estimates work far better than ranges for those purposes. Point estimates based on use cases would be a better solution, but it would be much harder to create and maintain. I need to make a lot of decisions with this blog as to where to invest my time (and Nick and Stephen’s time too), and I’m not interested at this moment in investing in such a large project. The problem isn’t just creating the estimates, but rather in displaying them in a useful way. Our credit card database and displays are setup right now to expect a single point value estimate. Anything different would be a lot of work.

The RRV fix

Over the weekend, Nick and I discussed this in detail. Rather than try to generate brand new cash value estimates, we decided to improve our RRV calculations in ways that would make the values more useful when comparing card spend rebates. Specifically, we made the following adjustments:

- All airline mile RRVs were adjusted downward by 7%. This is intended to approximate the loss in earned rewards for those flights. Previously we calculated that most airline Miles are worth 1.4 cents each. Now, we’ve reduced that 1.4 value by 7% to 1.3. Similarly we used previously calculated values for the rest of the airlines (see: What are oddball airline miles worth?) and reduced those values by 7%.

- We did not make a similar adjustment to hotel values because there are two counter-weighting factors with hotel RRVs which were based on observed hotel prices compared to observed point prices: Our RRVs are arguably too high because we don’t account for the fact that you don’t earn hotel points on award stays; and our RRVs are arguably too low because we don’t account for the fact that you usually do not pay taxes and fees on hotel award stays. A simplifying decision is to assume that those two factors cancel each other out.

- We changed our adjustments for transferable points programs. With transferable points currencies there is a much larger pool of high value awards one can pick from. So, we assume that a reasonable award value for informed consumers will be higher for transferable points. Previously we accounted for this by simply increasing the standard airline RRV at the time (1.4) by 30% for all transferable points programs. There were two problems with this: 1) 30% was arguably too big of a bump; and 2) we treated all transferable points programs as being equal. Now, we use the adjusted airline mile RRV (1.3) and adjust upward differently based on our subjective assessment of each transferable points program. We then rounded each one to the nearest .05 as follows:

- Amex Membership Rewards: 20% increase = 1.55

- Chase Ultimate Rewards: 15% increase = 1.5

- Citi ThankYou Rewards: 10% increase = 1.45

- Capital One “Miles”: 10% increase = 1.05 (based on standard transfer ratio of 2 to 1.5)

- We lowered the Hyatt RRV to 1.5. We no longer have a data driven source for Hyatt point values, so we instead lowered this value to match the Chase Ultimate Rewards point value. This makes sense to us because Chase Ultimate Rewards points are transferable to Hyatt 1 to 1.

While none of the above RRV changes alter the nature of RRVs, the RRV values were reduced to where Nick and I feel reasonably good about them being used for the purpose of comparing point rewards to cash rewards. No, it’s not perfect, but nothing is.

With the above changes in place, we now see that earning 1.5X Ultimate Rewards points equals 2.25% rewards based on RRVs. That seems about right.

| Card Info Name and Earning Rate (no offer) |

|---|

Earning rate: 5x travel booked through Chase Travel℠ ✦ 3x dining ✦ 3x drugstores ✦ 2% cash back total on qualifying Lyft products and services purchased through the Lyft mobile application through 09/30/2027 ✦ 1.5X everywhere else |

You can view all of our Reasonable Redemption Values by clicking here.

[…] 1.33c per point. According to Greg’s work, you’ll likely get more like 1.43c each, but we adjusted airline miles downward in May of 2019. If you do get closer to one and a half cents per point, you’re darn near even in terms of […]

[…] transfer partners. Shortly after we made major changes to our Reasonable Redemption Values (See: A big change to Frequent Miler’s point values.), we published a post on easy ways to get good value out of Citi ThankYou points. Today, we look at […]

It seems to me that “all airline miles are worth the same” is an oversimplification. It’s quite difficult to find cases where Delta miles are worth more than 1.2 cents per point. Southwest miles are worth at least 1.4 cents per point without much variance. BA miles (used for nonstop AA or AS flights) are often worth more than 2.0 cents per point.

Also, with both airline miles and hotel points, the consideration that you don’t earn miles on stays paid for with points is best kept separate from the value of the points themselves. Otherwise, every time you use a valuation, you need to back out the assumed value of the points not earned and replace it with the actual value — which could be nearly zero if you are paying for a ticket for someone else, or for travel on an airline such as TAP Portugal which gives no points for most coach tickets.

I think it is worthwhile to have valuations for deciding to earn a point to guide purchase decisions (especially for MS) and valuations for spending points.

For earning points, I use cash or travel redemption values (with travel I also back out forgone CSR earning). So for earning I use:

TYP: 1.21 cpp

MR: 1.25 cpp (Schwab)

UR/WF: 1.42 cpp (with 1.5 from CSR and WF Sig)

Hilton I use 0.4 cpp and Marriott 0.7 since there isn’t a good way to convert to cash.

[…] valuable than Chase or Amex points when we recently updated our Reasonable Redemption Values (See: A big change to Frequent Miler’s point values.), ThankYou points still have plenty of great uses (some of which are shared with those other […]

In the absence of an open market for points, it’s impossible to determine a correct point valuation. There should be some discount from expected RRVs to account for the lack of flexibility, more restrictions, lack of interest/appreciation (indeed a certainty of depreciation), and higher overall risk of holding points relative to cash, but exactly how much depends on each individual preferences as well as balances. Utility theory tells us that the more you have, the less valuable each incremental point will be worth to you, so if you have millions of AA miles, you would likely happily sell a few 100k at 1.2 cpp, but if you only had 100k AA miles then you probably would not.

I try to ask myself at what price would I be willing to buy some points, and at what price point would I be willing to sell some. Somewhere in between there is my valuation.

Just want to say thank you for putting miles in quotes in Capital One “Miles” – it drives me insane that they call their points miles. It seems obvious that it’s just to mislead people are aren’t as familiar with the concepts of credit card points and airline miles, and it’s completely deceptive.

Extra ironic now that you can exchange 2 Capital One “miles” for 1.5 airline miles. Wait, but if they’re miles (as Jennifer Garner would have you believe), shouldn’t it be 1 for 1???

Great post!!!!! Lots of brain work in this. Thank you so much!!!!!

[…] you’re thinking about a Princess Cruise, this is an awesome return on spend. This morning, Greg wrote about our newly-updated Reasonable Redemption Values. Based on our newly-calibrated valuation, that puts […]

Yup, All were too high. But Delta deserves special ignomy for Skypesos – they are worth a cent, at most. Simply ridiculous redemption values unless you find a sale.

Think you have the pecking order correct for transferable currencies (Amex highest, Cap1 lowest), but I’d argue most are still too high – it’s much harder to find good redemptions unless you base your travel on points destinations, which is a terrible reason to travel (like flying all the way to the Maldives just to sit on a beach – something that can easily be done in the Caribbean/Hawaii for a fraction of time/cost/environmental damage). Thankfully the number of bloggers gushing over the Maldives has dropped dramatically once they all did their obligatory 17-post series – ‘free’ travel – all we had to do was spend 2 days getting there, a $500 boat ride, pay hugely expensive food costs and we sat on a beach! But we were ‘saving’ $1000 a night! Smh)

This hobby is a victim of it’s own success. Guys like you making a living discussing this stuff is proof…

MSer

No one does that they and ME take what others are doing and adjust it for their travels .The blogs are a Gold Mine if u can get the drift how award travel works . I had like 50 or 60 $20 nites in 4* or 5* hotels .. The deal is that’s nice u got Free Air and hotel BUT most have no money to spend once they get there or need to pay basic bills so their not interest in any of this.

Take Care !!

CHEERs

Great post. I do think Hyatt (and all partners) need to be lower than their CC point transfer-partner to reflect the lost optionality when transferring to a program (vs. leaving as UR, etc.)

I understand the logic, but if someone has no interested in staying at a Hyatt (say they’re a Marriott loyalist, or trying to stay in locations that don’t have Hyatts), then in the situation where Hyatts are generally worth 2 cpp, it could make sense to have UR at 1.5 cpp and Hyatt at 2.

“Point estimates based on use cases would be a better solution, but it would be much harder to create and maintain.” 100% correct & is why no blog writer has yet offered the best data available for reader’s use.

You “upgraded” MRs, for instance, because your use for them is outsized value on airfare purchases. But you wouldn’t do so if you were only interested in hotel redemptions with MRs.

Separate value categories for hotel; air; cashback; & travel portal redemptions are needed for comparing apples-to-apples. Maybe someday, someone will find that time. Seems intuitive it will one day happen, though, since good redemption is the base objective to every post written.

Yeah, I think it’s important to distinguish between two related concepts: (1) What redemption value should I be getting? And (2) What card should I use for a proposed purchase?

I agree that the second question is essentially the same as deciding whether to buy points. The way that I think about is: at what point am I at equipoise whether I would rather have cash or have the currency? This number changes over time.

After redemption options, the single most important factor to me is my current balance of each currency. If I’m flush with Chase points, I’d generally rather have cash, so the point at which I’m a buyer of chase points is lower. If I’m low on Amex, they take on much greater value, because the ability to top up instantly to book an award that might come and go quickly is very important to me.

I think the key to all of this is to set some kind of baseline for the best value you can get spending $1 in a nonbonus category. For those with Ban of America deposits over $100,000, maybe that’s 2.65 cents. For those with the Amex Blue Business and a business plat who redeem with the 35 percent kick back, it’s closer to 3.00 cents.

For me, I have an Ink card that gets 5x at office supply stores. So, my baseline for nonbonus spend is buying $300 Visa gift cards with a $9 fee. I know that, unless I have a crazy surplus, I would always buy chase points at 1.5 cents per point, at least until I get a certain amount. A $300 gift card costs me $309 delivered to my door, and I get 1,545 points, which, at 1.5 cents per point, is worth $23.18, minus the $9 to acquire, or $14.20. That’s about 4.73 cents per point for that $300, so that’s my baseline. I need to beat that to use another method.

While this is a great post there is too much navel gazing going on. It’s better to earn some rewards but not the maximum rewards possible. I have tried to maximize my rewards earning but screwed my stock investing which would have been a lot more lucrative. All the dumb idiots trying to spend their points for 2c instead of 1.5c, hopefully you don’t expend any extra energy. That energy is better spent on your career, investing in stocks or chasing skirts.

Treat this as picking the low hanging fruit. If you can get it easily take it. Anything that needs more effort like getting multiple cards, tracking the best card, reading fine print on amex offers, reading and commenting on blogs is a waste of time. You won’t make enough to justify the time spent. This post is the realm of too much time spent and not worth the effort. Frankly get the best card for top 3 categories of your annual spend and a good cashback card. Keep all 4 cards in your wallet and evaluate once a year which card do you need to update.

KISS people KISS.

Yup made $900 before I looked @ FM and cut the lawn too. If the card works for YOUR travel not others get it .

KEEP IT SIMPLE STUPID !!! ( KISS)

CHEERs

CaveDweller: Please do not post political messages here. I deleted that part of your comment, but in the future will delete the entire comment if I notice political messaging.

Oh ok sorry Greg !!

CHEERs

You make some good points, and that’s probably the right philosophy for you, but not for everyone. It reminds me of Elon Musk saying that grad school is a waste of time. Yeah, maybe for him. But not for everyone.

Let me give my example. I’m a husband and a father to 3 kids. Also a military reservist and a grad student. And i churn/MS as one of my hobbies. I find it to be a constructive way to spend some of my time with something that helps my family, without having to think about work or school. And I’m not playing the stock market because that’s just too risky for someone in my boat. Totally happy here just taking my family on trips with points and miles through this game…much less stress thank you very much.

That depends on how much fun you have making these calculations (a lot if us ENJOY this) and how much money you can otherwise make with that time.

You should really be encouraging everyone to calculate their own point values based on their own usage. RRV’s are a great starting point for people who are new to the game or new to a particular point program, but once folks have a few redemptions under their belts they need to tailor their values to their own tendencies. It sounds obvious, but I’ve met a few people who never thought to do it, or simply never bothered.

Fully agree, we are all individuals. Greg’s words: “… points are worth more or less based on how they’re used, how many you already have, how easy they are to use, whether or not they add value (such as free flight changes), whether or not you have elite status, your travel habits (e.g. airline miles are often worth much more on international premium cabin flights), and your subjective value of the “joy of free.”

For me, great experience with United and American reservations, the help they give me getting first class seats when we take our trips, which we’ve worked hard to save for, means so much, that I often focus on earning their miles over other choices – because it’s easier to build and then travel than to mix cash back and such. The same for Hyatt – being able to give my wife a high end room in NYC for her visit with a friend, where the manager greats them in the lobby with a gift (!!!!), priceless, you can not calculate the point value. Our family observes that we are treated far better when visiting hotels on points – with our higher status levels – than we are when paying cash, it happens time and time again.

I totally agree with you on Hyatts. I’m primarily a Hyatt person, and I regularly get 2cpp+ all across the spectrum. The fact that I can sometimes even get 3-4+ means that 1.5 is just too low of a value *for me*.

Cat 1 HH/HP/HR – these are hotels that regularly cost $100-$150, so I’m getting 2-3 cpp (and getting free parking) in addition to normal benefits

Cat 4 – This are frequently really nice midrange hotels. Some of the really sweet spots went away, but at 12K points/night, I would have otherwise paid $400/nt for HR Bonita Springs, $500 for Centric San Francisco and more.

Cat 6/7 – This are frequently very nice hotels in expensive locations. Andaz Hawaii at the previous 25K points/nt had a room rate in the $600/nt (not to mention, free valet, waived resort fees, etc).

Few of us redeem often enough to do so. It’s important to have baseline valuations to help determine whether a specific redemption is wise.