Nick recently wrote a couple of posts where he argued that Chase Ultimate Rewards points “ain’t all that” (here and here). As I thought about writing a rebuttal, my mind kept drifting back to the need to correct a common misconception. It’s difficult to debate the value of points without first agreeing with the meaning of “value.” Commenters, bloggers, podcasters, whateverers often claim that the true value of an award is not the cash price of that exact flight or hotel or cruise, but rather the cash amount you would have been willing to pay if you had paid cash. That’s wrong. Wait, wait, wait! Before you raise your hackles (it’s been a minute since I’ve used that term!) let me explain that your concept is right, but you’re using the wrong word. The correct word is “savings.” When you spend 100,000 points to fly international first class, your savings are correctly accounted for by the amount you would have otherwise paid for a flight. Let’s say that you would have been willing to spend $1,500 on an international flight if you hadn’t found that 100K first class award. It is absolutely correct to say that your 100K points resulted in saving $1,500. Boom. Done. No argument from me. But if you try to claim that the value of the first class flight was only $1,500, I vehemently disagree. My hackles are raised.

A long, long time ago, my favorite angel of darkness, The Devil’s Advocate, made the same argument that I’m bringing to you today. In that post, he imagined a scenario where it would have been possible to buy a brand new Porsche with a million Delta SkyMiles. Sure, he wrote, you might have only been willing to pay for a Hyundai, but: “You didn’t get a Hyundai. You got a Porsche.” Exactly. Returning to the term “savings,” you saved the $20,000 (or whatever) that you would have spent on your Hyundai, but what you got was much more valuable. The same is true when you use miles to fly first class. You might not have been willing to pay cash for first class, but you still got first class value.

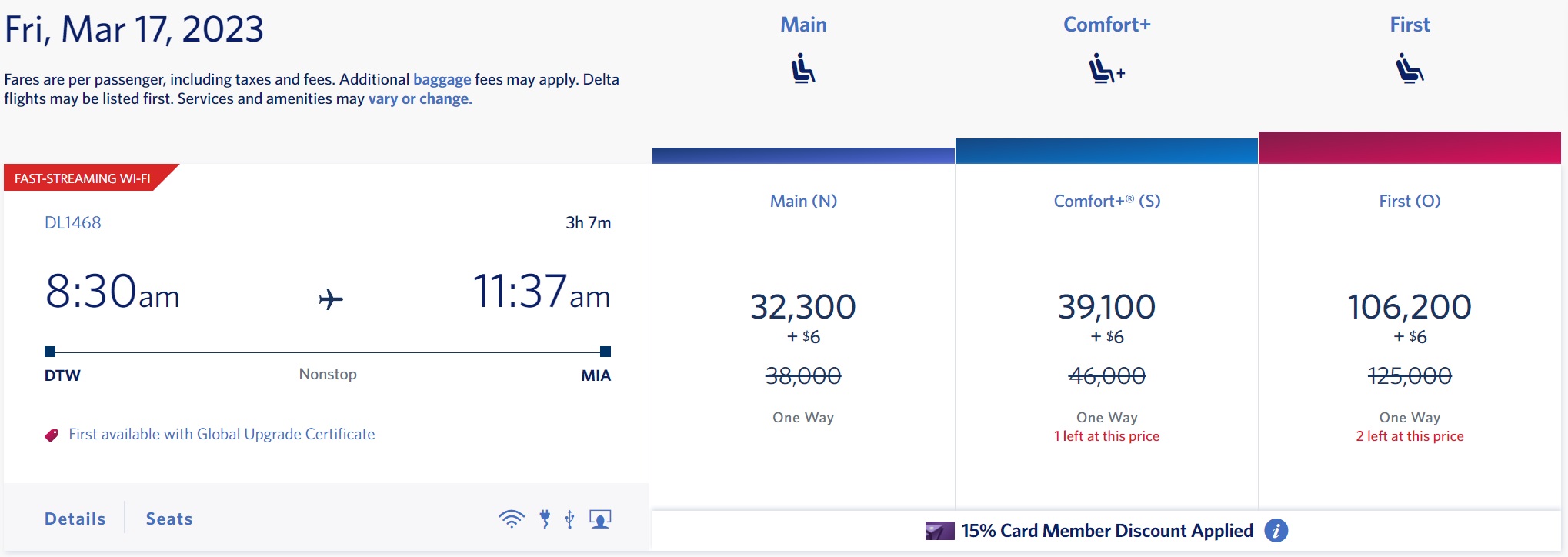

Let’s now dial this down to a much more realistic everyday example. Let’s say that you’re looking to fly economy from Detroit to Miami and you found the following nonstop flights that work with your schedule. Both prices are for regular economy, not basic economy:

- AA departs at 6am: $299

- Delta departs at 8:30am: $484

You don’t really want to have to wake up at 3am to catch that 6am AA flight, but you figure that the savings are worth it. Then you do an award search and find that you could use your Delta miles for the preferred 8:30am flight:

As you can see above, a Delta cardholder can pay 32,300 miles + $6 (really $5.60) for the Delta flight. My argument is that those 32,300 miles plus ~$6 result in $484 in value, but only $299 in savings. The value per Delta mile is 1.5 cents per mile, but the savings per Delta mile is only 0.9 cents per mile.

I can imagine people arguing that they don’t personally value that Delta flight at $484. Well, OK, but now you’re getting into a whole different ball of wax where you’re talking about subjective value (alternatively, let’s go with a “ball of yarn” for those cats to play with). If you want to argue that the subjective value of your Delta miles are less than 1.5 then go for it. But then keep in mind that cash would also have a subjective value. For example, maybe you don’t have any miles and so you might pay for the $484 flight with cash because you really can’t stand the thought of getting up too early. In that case, you might declare that the flight was subjectively worth only $300 to you. But then you would be indirectly making the argument that your dollars are worth less than dollars. That doesn’t make sense. For this reason, I don’t see a place for subjective value when arguing about the value of points.

When talking about objective value, there’s simply no better way to objectively value something than to see what that thing is actually selling for. There are reasons that Delta can sell that flight for more than AA does for theirs: Delta’s flight is at a better time, Delta is more reliable, Detroit flyers are more likely to be loyal to Delta, etc. But ultimately, those reasons don’t matter. The objective value of that flight is the amount that Delta sells it for. Full stop.

As an aside, basing the value of an award on the cash price often undervalues your award a bit because the award is often fully refundable whereas the cash ticket usually is not. For example, with a Delta award flight originating in North America, you can cancel it and get all of your miles and fees back. With a paid flight, you’ll get back a credit which expires in a year. That’s not as good. On the flip side, the paid flights earn miles whereas the award flights do not, so you can either decide that these two issues cancel each other out or account for the loss of earned miles when figuring out the value of your miles.

Caveats…

When comparing the value you got from your points and miles to the objective value, I recommend following these guidelines:

- Record the cash price at the time of booking. If you booked a flight six months ago with airline miles and just the day before your flight think to look up the cash price, you’re very likely to see a much higher price than you would have paid back when you booked your award.

- For one-way flight awards, record the round-trip airfare and divide by two. Sometimes prices for one-way flights (especially international flights) are much higher than half the round-trip price. The same isn’t usually true when using airline miles (but it is sometimes true with Delta miles, FYI).

- With hotel and miscellaneous other awards, make sure to find the best available cash rate. For example, when booking a SLH property through Hyatt, Hyatt sometimes charges more than if you book directly with the SLH property. The lowest available rate is usually a better measure of value. I say “usually” because sometimes the lower rate doesn’t come with benefits that you would get when using points. For example, when booking an SLH property with Hyatt points, you’ll earn Hyatt elite qualifying nights for your stay. If that matters to you then the price for booking through Hyatt may be the better choice for assigning value.

Let the objections begin…

I eagerly anticipate fierce objections to my arguments. Please comment below…

![Hyatt goes next level with Mr & Mrs Smith [Integration “early 2024”!] a heart shaped sign over a house overlooking a body of water](https://frequentmiler.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Mr-and-Mrs-Smith-and-Hyatt-218x150.jpg)

“Value is not intrinsic, it is not in things. It is within us; it is the way in which man reacts to the conditions of his environment. Neither is value in words and doctrines, it is reflected in human conduct. It is not what a man or groups of men say about value that counts, but how they act.”—Mises

Love this article! And I totally buy your discussion.

“It’s not worth this because I only value it this much” completely negates the fact that things simply don’t cost what you value them at. Sure I’d love to value a first class flight on Emirates at $500, but that’s not reality. I might only value gas at $1.50/gallon but it doesn’t matter, or eggs, or whatever it is – it costs what it costs.

It also overlooks the fact that someone may not be willing to take the cheapest equivalent flight. My vacations are limited, and I want to be comfortable when traveling. If an economy long haul flight to get somewhere is $500, I would never pay $500 because I’m simply not going to take an economy long haul flight. I value that at zero because I won’t do it. So again we look to the cost of the flight I actually took as the comparator, not the cheapest alternative with 14 connections. 😉

Great post!

[…] in line with its actual value to you. That is the most important factor in weighing this decision. (This article explores the savings vs value debate much more fully than I am capable […]

As an economist, I love to debate things like this, but I think this ongoing argument is overcomplicating things.

If in a world without points, I’d have booked the exact same thing for cash, I put down the cash price. For things more extravagant or convenient than I would normally pay for in cash, I determine what I would pay over the cheaper alternative I would have booked in a pointless world to make me indifferent to the cheaper option. Done.

Only using retail price and claiming your United miles are worth 5 cents each falsely equates price with value/benefit, while separating savings vs value perhaps helps illustrate the concept, but seems to add effort without adding informational value.

Great article to spark discussion!

Though I’m not sure I would agree with your point on value. Take your Porsche example. If, say, someone was gifted a Porsche that had a sticker price of $100k. Did he receive $100k of value? Maybe. But it would depend. Assuming he would be able to sell/liquidate it for $100k then, yes, he definitely received $100k in value. If the terms of the gift required him to retain the car without any option to resell it, then I would argue that in some cases he would not have received $100k of value. If he recently bought a Bugatti and and has no use for a Porsche, and would leave that Porsche sitting in his garage, with no option of selling it, I would argue he received much less than $100k of value, and potentially even zero or negative value.

Value is relative, and depends on the individual receiving that value. An other way to conceptualize it is in terms of the stock market and corporate acquisitions: why is Company A willing to pay more (than Company B) to acquire Company C, assuming they both have deep pockets? Simply put, because the value of Company C is greater to Company A than it is to Company B. Value depends on a discount rate that varies from person to person (or company to company).

I can’t agree with any argument that would result in the Amex Platinum Equinox credit being a “$300 value”.

Let’s suppose a one-way business class ticket to Australia is 100,000 miles going on either Monday or Tuesday, while the cash price is $10,000 on Monday, but only $6,000 on Tuesday. Thus to get the biggest savings you will certainly fly on Monday, right? Why would you pass up the $4,000 in savings?

Actually, no I don’t hink you would care. The cash price isn’t doesn’t become relevant until it approaches the range where you would consider paying cash, such as in the Detroit flight example.

That’s not to say it isn’t good to book premium awards if that’s what you really want, just that the nominal cash price doesn’t matter when it is substially above what you’d ever consider.

I’m impressed that it’s only February and you already have the front-runner for “featured image of the year.” Bravo.

While I appreciate the effort to provide clarity to an oft-discussed topic, the conclusions of the article fail to do so; applying layman’s terms (like “subjective value” rather than simply “value”, or “objective value” rather than “market price”) to redefine economic principles only convolutes things further.

What’s missing is a big-picture discussion of WHY the “value = asking/sticker price” perspective is problematic in the points travel hobby.

Most of us can agree that traveling via points can be described as a game of “cat and mouse”, in which prospective travelers are constantly making adjustments to evade the ever-changing actions of travel service providers and the financial institutions they used to encourage cashless travel purchases.

In that respect, it’s worthwhile to consider that transactions involve “price-makers” and “price-takers”. When travelers are playing this travel game well, we reject the notion that we must pay “sticker-price” for airfare, hotels, etc…in short, we reject the price that many/most others take for granted, and instead “make” a price for ourselves by finding alternative ways to purchase the same or similar goods and services. Granted, we are still “taking” the lower price, but the often-significant effort in finding a good points redemption should be distinguished from accepting a cash list price.

Like any seller, airlines and hotels would *love* for consumers to (a) pay higher list prices, and (b) remain loyal to their offerings rather than shop for similar “substitute goods” provided via another airline, hotel, or OTA. Simply put, the service providers want to be price-makers, and they want us to be uncritical price-takers.

And there’s the irony…when we choose to calculate our redemptions based on inflated prices that only reflect a single purchasing option in a brief moment in time (rather than taking the total market into consideration), we are the proverbial “mouse” defining the game on the “cat’s” terms, as if the lower-priced alternatives don’t exist!

Rather than falling into this mental trap, those who advocate the “next most likely alternative” cost model seeks to define a redemption from the *consumer’s* perspective…what we’d have otherwise paid for a similar service if we had to pay with so-called “real money”. The concept is similar to “BATNA” or “best alternative to a negotiated agreement” discussed in the best-selling book “Getting to Yes”, and stresses that better outcomes can be had when we reject traditional means of thinking about agreeing to a price.

So, do we want to discuss “value” in a way that supports an industry that works very hard to create “information asymmetry” (where one party benefits from keeping the other in the dark about the true cost of a good or service)? Or do we insist on establishing a reasonable baseline cost model…one that helps our fellow prospective travelers answer the question “which of these options is right for me”, as opposed to “which is a theoretical greater savings on a price I likely wouldn’t otherwise pay”?

Thanks for your thoughtful comment, Ed.

I especially appreciated your objecting to using as a measurement of value “prices that only reflect a single purchasing option in a brief moment in time (rather than taking the total market into consideration)”. That’s spot on.

To elaborate a bit further, the objective of what you call the “price-makers” here is generally to maximize aggregate revenue across their entire inventory, whether that is first-class seats, hotel rooms, or rental cars in a fleet. And achieving that goal implies a range of pricing, not a single price (to which some notion of “value” might then attach.) For example, take long haul first class seats:

First they sell them as paid FC, pricing at say $10k per ticketThen they release seats for points redemptions and to partners, at say $2k in value on averageIf there is less room in economy than in first as the flight draws closer, they may sell paid or award upgrades at say $1k a ticket\If seats still remain after all that, they may clear systemwide upgrades (or the equivalent) gaining $0 marginal dollars, but gaining elite customer goodwill.And the pricing on all of 1-3 will typically vary considerably before the flight occurs.

Articles like this and their comments sections highlight why “value per point” is a useless vanity metric. It has no practical purpose.

What matters here in my subjective value of the redemption, but it is impossible to know. The key insight of economics is — people don’t know their “willingness to pay”, they can only decide whether to buy (yes/no) at a given price given their circumstance and alternatives. The subjective value for the redemption is higher than (or equal to) the savings, but impossible to put a number on.

So, what matters is how YOU simplify the decisions you have to make. In my case, I do this:

1. Convert all options to cash equivalents. I use acquisition cost of points because I feel I can generate more points when needed for future travel (thanks to points & miles games). If points are scarce in your case, use the typical redemption value.

2. I ask myself: which option would I rather take? Cash equivalent price vs subjective value. The choice is based on various factors like travelers, occasion, destination, comfort, which side of the best I woke up on, etc. Subjective.

3. I buy it (or make the award redemption if points). I never ask myself “how many cents per point” I got. The cash price for the points redemption is irrelevant.

Question for people here: does anyone here actually decide based on cents per point? If the Delta flight was $4k instead of $484, would you become more likely to choose that redemption??

Not me. I go for convenience and best schedule for me. Cents per point is an afterthought.

Exactly!

Your “value” seems to be only applied after the award is booked. At that point the valuation is skewed, because points/miles biggest limitations, limited scope of use (compared with cash) and very limited availability (compared with a cash ticket), are no longer issues. The valuation of points is evaluated before you have a booking, and it is simply the point price for how much you would be indifferent between buying and selling. This is fairly non-controversial if you ever took econ 101.

What you choose to value your redemption at is only relevant for bragging and for deciding whether a particular redemption is a good use of your points, which of course depends on the person. This is where your RRVs come in, but they are by no means indicative of “value”. If you’re using that to measure “value”, then you are subscribing to the late night informercial method of valuation.

I love your blog. And podcast. I consume them both with gusto and appreciate all of it. Sincerely. This is an intellectual discussion, please do not take this as argumentative or otherwise too seriously.

But, respectfully, I disagree. Beginning with the title, where you rather boldly assert that the actual definition of ‘value’ in mainstream economics is incorrect. Debates of this kind can’t happen unless people agree on terminology (philosophers will say). I’m siding with the economists, partly because, to be honest, your definition of value smuggles price into the (operational) definition of value. This biases value in a way that makes flight and hotel bookings appear more valuable than they actually might be. That would certainly be true for people who just want to get from point A to point B and don’t care to shower on an airplane or what have you.

Also, you can pretend all you want that a gray market for buying/selling miles doesn’t exist, but it surely does exist. And there is a going rate for every award currency. Sure, that market is extremely segmented, and the rates may vary wildly based on what small subset one has access to, still, for anyone reasonably involved in this hobby, the range of market rates (or the internal between typical buying rates and typical selling rates) will be much much narrower than the internal between acquisition cost and airline-assigned “value”. A glimpse into the market would offer a much better idea than the approach outlined in the article, and better than the reasonable redemption value approach that you came up with years ago.

One issue with this is that the buyers are typically middlemen rather than end users, meaning, they, in turn, charge the end users higher rates for award tickets they book. They may find outsized redemption opportunities and people willing to take the risk in exchange for some savings relative to airlines’ fare. But those are travelers not concerned with miles at all – and I’m not sure that they need to be part of the equation.

I think the idea of an opportunity cost is once again so important here. It matters a lot for how we think about valuing points and miles.

I think Nick makes a great point about what your value/savings on a flight/hotel implies about your willingness to acquire points at a certain cost. I’m flying to Australia in Business Class on Etihad in a month or so. The flights would cost me ~$19k round trip and cost me 220k Aeroplan and maybe $150 taxes and fees. My Aeroplan points are “saving” me almost 9 cents per point. Fantastic! I’m really enjoying this because I get to go to Australia and in a much more comfortable way than I ever could have imagined without this hobby. You could say the points are “worth” 9 cents per point because I have a way to redeem them for 9 cents per point, but would I buy membership rewards points for up to 9 cents per point? Absolutely not! That implies that they are not “worth” 9 cents per point to me. There are many reasons for this, of course the most prominent being that I don’t have unlimited amounts of money to exchange. Money feels scarce, and points earned through the hobby “feel” free (even though they’re not, for reasons we’ve discussed here before).

When people talk about “value” in this hobby, I always take that to mean that there is a difference between the cost of an experience (flight, hotel, etc) and its value to you. Does it really matter to me that Etihad is charging $19k for this itinerary? Absolutely not, because I never would have paid for it. Can I say I’m getting a $19k experience out of this and not be wrong? Absolutely, but where it matters is what that implies about the decisions you’d make. I think you’re both right: I could say I’m “willing to spend” $2000 or so on this experience–which I am by not cashing out these MR points–but I’m okay with that because I’d much rather pay $2000 to sit in business class than be in economy for 24+ hours to go to a bucket list destination.

But, if in some fantasy world Etihad were charging $2000 for this itinerary, then we might have a conversation. Should I really be spending 220k Aeroplan/MR points if it’s only going to save me $1850 on this trip in this made up example? I probably wouldn’t. Why? Because then I could acquire the same experience in a more efficient way assuming I could cash out MR for 1.1 cpp at Schwab. It wouldn’t make sense to spend those 220k points just because there was availability on Aeroplan. What this says is then there is some middle point (which I couldn’t precisely identify) where I feel like I’m getting enough outsized value from these points (value in my terms here would be over an easily accessible outside option, aka an opportunity cost of redemption, like 1.1cpp to Schwab).

This is a great discussion line for bringing to front of mind a number of “valuation considerations”. So Greg, I am wondering if you are a buyer of MR Points at 1.55 CPP?

Implicit when valuing a sign up bonus with the model ((b*cpp)-fee): [total points times the cpp rate less the fee]; is purchasing MR at 1.55 cpp. For example, 150K MR at 1.55 cpp = $2,325, less fee of $695 = $1,630. If in the alternate, you were only willing to buy MR at 0.75 cpp, the valuation result in the above example would be $889. This result is obtained as follows: {(150,000-($695/.0075))*.0155} The proof is to substitute 1.55 cpp for .75 cpp in the formula. Doing so confirms the model ((b*cpp)-fee) implies purchase of points at 1.55 cpp as an offset to the fee.

Once one starts dissecting valuation models, the next most obvious question is what about the value of perks received that may reasonably offset the fee. Obviously the answer to that is highly circumstantially dependent. For some, the value of perks more than offset the fee. If that were the case, valuation would simply be (b*cpp). However, for those of us with nth Business Gold and Platinum cards, there is limited opportunity to easily obtain marginal value from the perks. In such a circumstance, it becomes material to consider the implicit purchase of points in the process of evaluating competing opportunities.

I appreciate the complexity level can become exponential quickly in developing valuation models. Nonetheless, many people may not be aware of the implicit assumption of purchasing points contained in the base valuation model. As such, some level of disclosure/discussion of the impact may be worth consideration.

PS: I suspect you may have already surmised, I have developed a model that considers all the elements discussed above. I would be happy to forward it to you upon request.

I’d like to see the model.