A reader, whom I’ll call Bob to maintain anonymity, recently sent us an email that expressed what I imagine is not an uncommon sentiment, at least among those new to this hobby (and probably even among some of those who have collected points and miles for years):

Hi all. I’ve been watching your videos on YT and reading your blogs. I’m new to the hobby and trying to learn but all the ninja math valuations lose me. If the purpose of the game is to amass points that we can use for great travel, then why can’t that just be enough? I’m genuinely asking because I’m trying to not become discouraged. You guys have taught me a lot but I’m having a hard time caring about how many tenths a cent per point….blah,blah. I’m building a stash of Amex points. So far approximately 90K. How many should I get before I try to book? I just want to take fun trips.

Our reader here actually has two separate but important questions:

- Do we really need to do the math? (i.e. Should we really care about tenths of a cent per point? If so, why?)

- When should I start redeeming my points?

The second question is easy (or easier) to answer: when you have the points you need to book a trip you want and you are able to get a reasonable value for your points, go ahead and book it.

That second part is where the importance of the math comes into play.

You don’t have to care about the math

For starters, I want to recognize that you don’t have to care about the math. If you’re happy just getting some “free travel” now and again, maybe that is enough for you. While I certainly recommend doing the math, I know that not everyone will.

You may be happy with a vacation that feels “free” (or close to it) every year. In fact, there is a not-insignificant minority of miles and points enthusiasts whose mantra is to “never pay for travel”, even if it means accepting less value per point. Fair enough.

However, in my opinion, this is kind of like car shopping by saying, “I want this car as long as my payment can be $500 per month” and ignoring the purchase price / interest rate / term (note: I am not advocating in favor of taking out an auto loan, I am just using it as a comparison point that is familiar for many). Maybe you can afford the $500 monthly payment, but the term over which you’re making that payment makes a huge difference in your total cost (and therefore the quality of the deal you’re getting). Pay $500 per month over a 36-month loan, and you’ll pay $18,000; if the loan is a 48-month term, you’ll pay $24,000; total out of pocket will be $30,000 if it’s a 60-month loan. While some folks will be satisfied with a monthly payment they can afford and ignore the details, I would argue that doing so leads to a poor financial decision. The overall price of the car and the terms of the loan (if you’re borrowing to buy it) are much more important than the monthly payment.

To me, travel rewards are similar in that I don’t want to be making poor financial decisions based on prioritizing “free” travel over getting good value for my points in the same way that I wouldn’t want to prioritize a monthly payment over purchase price and loan terms for the car. In order to make good financial decisions, I need the math in both cases. While I recognize that some (many?) people will not care enough to do the math, I will always encourage people to do the math to maximize their situation.

A (relatively) simple example

You’ll hear this example on this weekend’s Frequent Miler on the Air podcast (in the Question of the Week section at the end), but I thought it was worth repeating here on the blog.

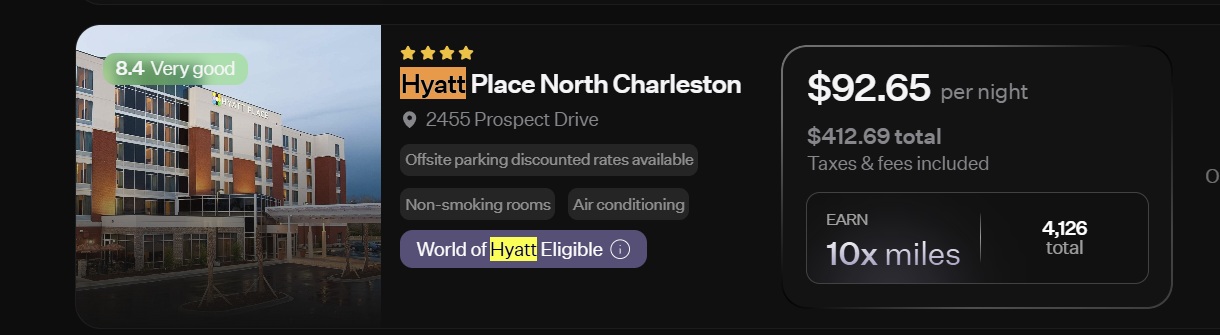

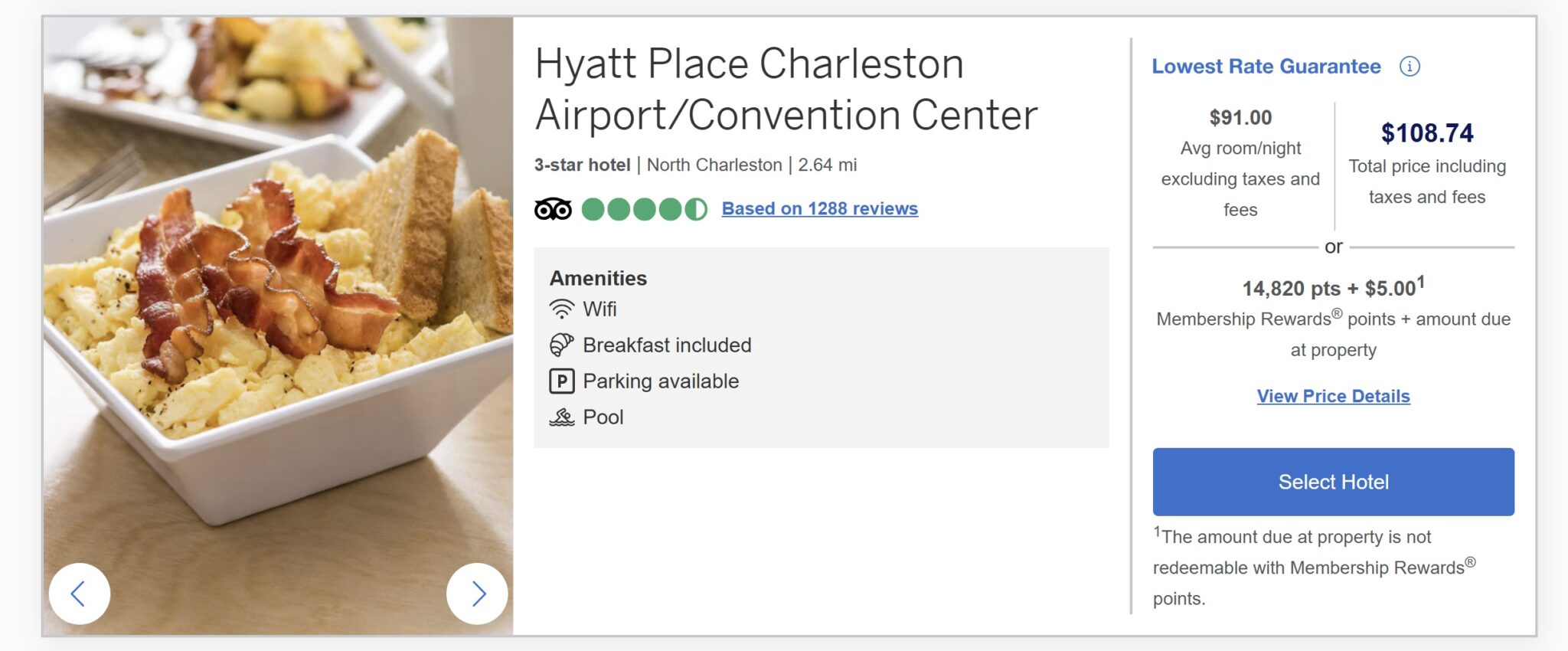

Let’s imagine that I planned to stay at a Category 1 Hyatt in North Charleston, SC. This is a real-world example for me, as I was recently eyeing a stay that would cost either 5,000 World of Hyatt points per night (standard rate) or about $100 per night with cash.

Let’s imagine that I wanted to stay there and that I anticipated $10,000 worth of dining spend between now and the stay. Which card should I use?

The Capital One Venture Rewards Credit card offers 2x on all purchases. If I put $10,000 worth of dining spend on this card, I would earn 20,000 Capital One miles, which I could use to erase $200 in travel purchases. That would be enough return for me to erase the cost of two nights at the hotel I want. Getting 2 free nights means a weekend getaway, which isn’t bad.

The Robinhood Gold card offers 3% cash back everywhere. If I put the dining spend on the Robinhood Gold card, I would earn $300 cash back (that’s 3% of $10K), which would be enough cash back to buy me 3 “free” nights at the hotel (which I am calling “free” since I would be using my accumulated rewards to cover the cost). With cash back on this card, I am up to a long-weekend away, which sounds better than a short weekend :-).

If I instead used the Chase World of Hyatt Credit Card, I would earn 2 points per dollar spent on dining, which would total 20,000 World of Hyatt points. While that sounds similar to the Venture card, it isn’t since Hyatt points could be used to book the hotel through Hyatt (remember that it costs 5,000 Hyatt points per night). Putting my dining spend on this card would get me 4 free nights at the property in question. In this case, the fact that I can get $0.02 per point in value toward this stay when using Hyatt points is important! It means that collecting Hyatt points will get me one more free night than collecting cash back would have. Four free nights beat three free nights, so I would choose the World of Hyatt card over the Robinhood Gold card. That said, the nights wouldn’t necessarily feel “free” to me since I am essentially accepting 20,000 points instead of earning $300 in cash back. It makes sense to choose points over cash in this comparison, but only when I am redeeming the points for more than $300 in value (in this case, the points are buying me four nights that would otherwise cost $400). If I used my 20,000 points to pay for a hotel stay that would have cost $250 in cash, then choosing to earn Hyatt points would have been a poor decision, comparatively.

However, I could alternatively use the US Bank Altitude Go card to earn 4% cash back on dining. That would get me $400 back on $10,000 spend. That is also enough for 4 nights at the same hotel — plus I’d earn Hyatt points on the cost of the stay (which is also true in the Robinhood and Capital One examples, but more salient here since it one-ups using the Hyatt credit card). If I were able to book this Hyatt stay via Rove Miles by 10/31, I would even earn 4,000 transferable miles from Rove on top of earning hotel rewards and getting my 4 nights “for free” via the rewards earned on the Altitude Go card. I would end up with four nights and at least 2,000 Hyatt points and 4,000 Rove miles. That’s better than just four free nights!

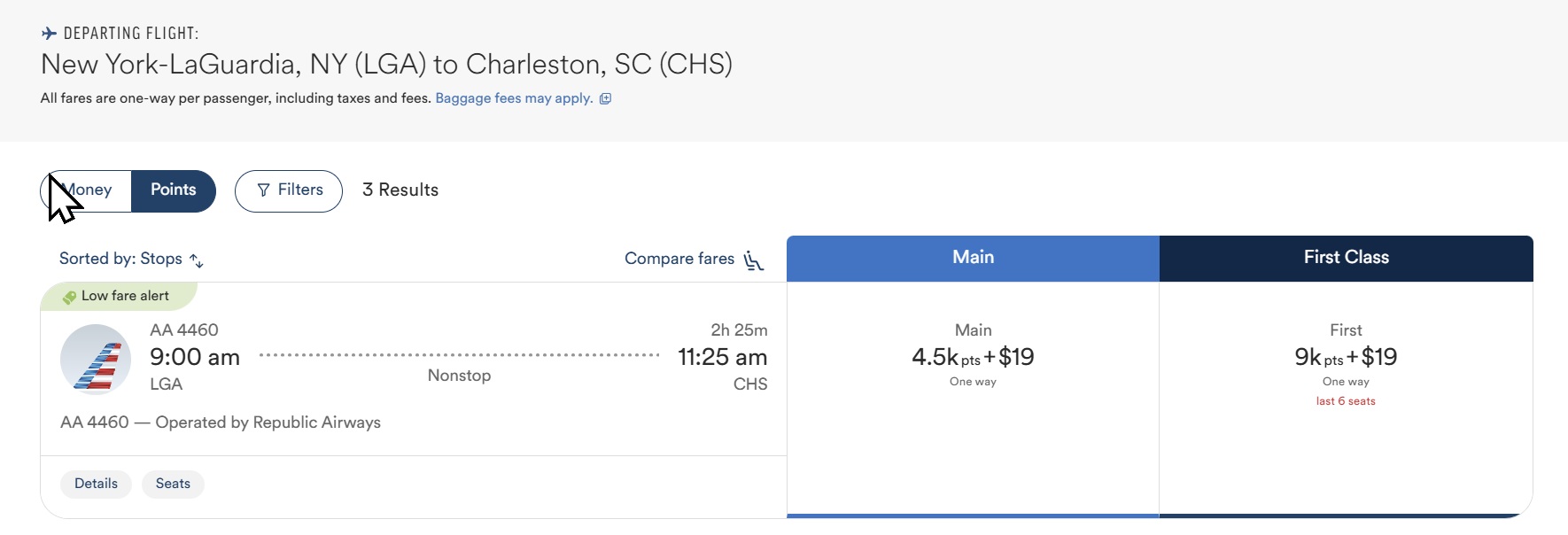

However, what if I used the Bilt Mastercard to pay for dining purchases? That card offers 3 points per dollar spent on dining, and then I could transfer points to Hyatt. I would earn 30,000 points on $10,000 spent on dining. That’s enough for six free nights at 5K points per night! That is double the “free travel” I’d have gotten with the Robinhood Gold card and 50% more nights that I’d earn by using the World of Hyatt card. Alternatively, if I only wanted 4 nights, I could just transfer 20,000 Bilt points to Hyatt and have 10,000 points left over with Bilt. As fate would have it, that’s enough points to fly round-trip to Charleston from New York City if I transferred my Bilt points to Alaska’s Atmos Rewards, which would actually cost just 4,500 Atmos Rewards points each way in economy class.

If I used the Bilt card for $10K in dining purchases and earned 30,000 Bilt points, I could literally fly to Charleston and stay for free for 4 nights (and have 1,000 points left over) using the same amount of spend demonstrated in the other examples (do note that I’d pay taxes on the award tickets, but it wouldn’t be much here). That is far more travel in exchange for my spending than I’d have gotten with the Venture card or Robinhood card.

It may seem like the obvious point here is that earning more points is always better. Obviously, earning a multiple of 3x on dining is better than 2x. Therefore, earning 4x is better than 3x (and surely better than 3% cash back), right?

Not so simple.

Take the Amex Gold card, for example. That card offers 4x on dining, which would yield 40,000 Amex points — the most of any of these examples yet. However, if I wanted to stay at that Hyatt Place, I’d be redeeming points through Amex Travel at an abysmal seven-tenths of a cent per point ($0.007), meaning that a $100 night would cost me more than 14,000 points per night. I wouldn’t even have enough Amex points for 3 free nights! I’d have to settle for just 2 free nights with points left over (or the 40,000 points would get me $280 in value at 0.7c per point — less value than I’d have gotten with the Robinhood Gold card at 3% back).

But you might astutely point out that I could transfer my Amex points to Hilton at a 1:2 ratio. My 40,000 Amex points could become 80,000 Hilton points. Would that work out better?

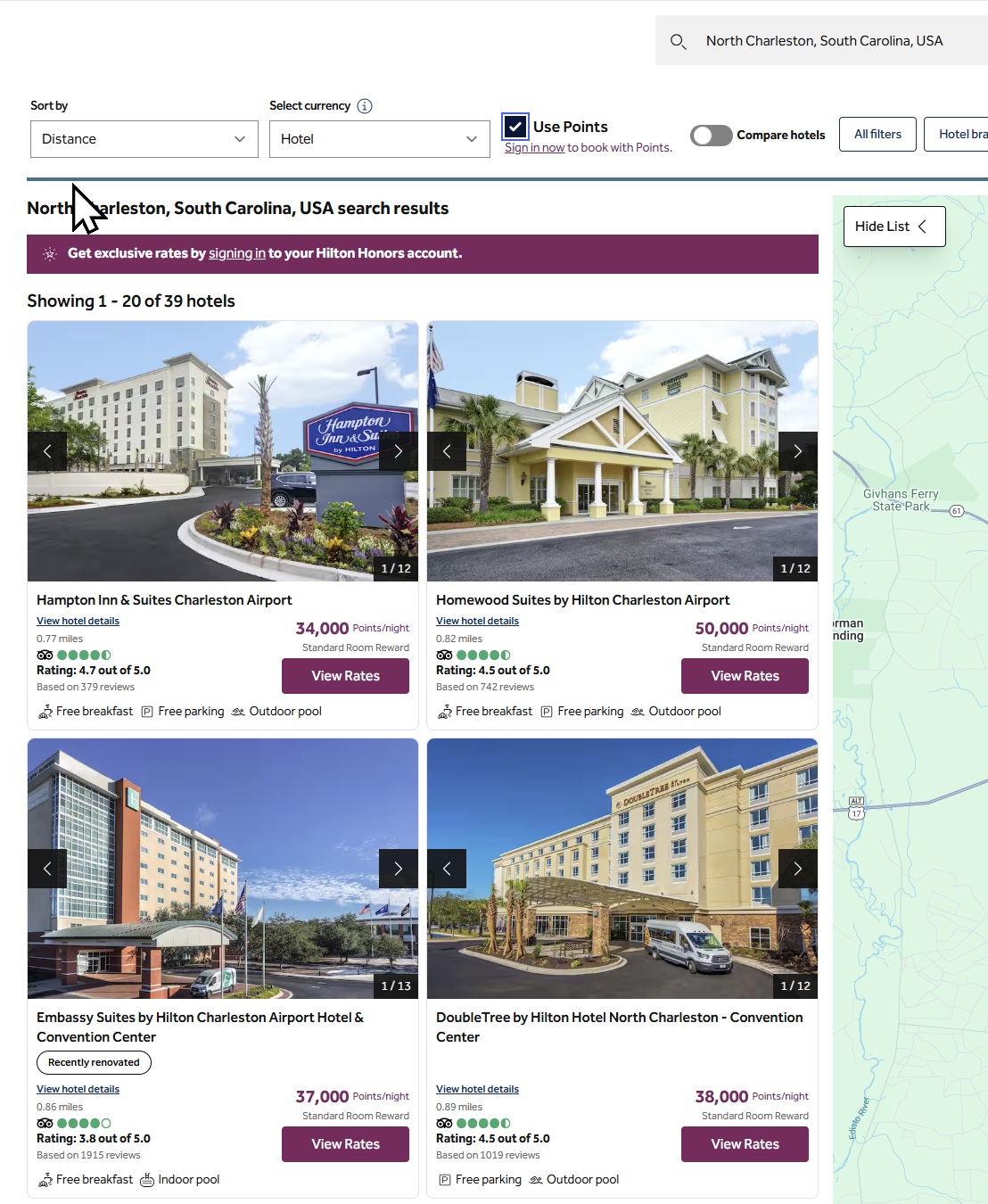

Sadly, it wouldn’t, as 80,000 Hilton points would get me 2 free nights in that area at best during the same dates.

Since I brought up Hilton, you might wonder if the Hilton Honors American Express Surpass® Card is the best choice for dining spend since that card earns 6x on dining. However, do the math: $10,000 in dining purchases would only yield 60,000 Hilton Honors points on that card. That wouldn’t even be enough for two free nights in North Charleston! I’d get 1 night with points left over.

In recap, in this one hotel example, $10,000 worth of dining spend would yield the following with each of these cards:

- Hilton Honors American Express Surpass® Card (6x dining): One free night at an alternative hotel with points left over

- Capital One Venture Card (2x everywhere): Two free nights at the hotel I want by redeeming miles for travel purchases.

- Amex Gold card (4x dining): Two free nights at the Hyatt hotel I want through Amex Travel using almost 29,000 Amex points (I would end up with 11,000 points left over)

- Robinhood Gold card (3% back everywhere): Three free nights at the Hyatt hotel I want, using the $300 in rewards I could earn on the Robinhood Gold card (plus at least 1,500 Hyatt points earned on the “paid” stay and as many as 3,000 Rove Miles)

- World of Hyatt credit card (2x dining): Four free nights at the Hyatt hotel I want, using the 20,000 Hyatt points earned

- US Bank Altitude Go card (4% back on dining): Four free nights plus 2,000 Hyatt points and as many as 4,000 Rove Miles using the $400 in cash back rewards I would earn.

- Bilt Mastercard: Six free nights using the 30,000 Bilt points I could earn with the Bilt Mastercard or four free nights plus round-trip flights! It is worth noting that you could also earn 3x on dining with several Chase cards and transfer to Hyatt, but I used Bilt in this example since it has no annual fee and transfers directly to both Hyatt and Alaska (which would work for flights).

A true comparison becomes more complicated — the World of Hyatt card has a $95 annual fee, but would also earn elite nights on spend and progress toward an extra Category 1-4 free night certificate; the Amex Gold card has a $325 annual fee and a bunch of coupon credits. We could add more complexities yet, but my point isn’t to get into the weeds with those right now, but rather to show that the amount of travel you can get varies wildly depending on the card and use of points. The math gets murkier still if you already have more Hyatt points than you’re likely to use any time soon; if you already have a million Hyatt points, you would likely value the chance to earn $400 in cash back more than the chance to earn Hyatt points even if you could theoretically use Hyatt points to better value since you won’t likely be doing so any time soon.

And in this case, even if you didn’t have any existing points, you might not think it makes a huge difference between earning rewards that can get you 2 free nights or 3 free nights, or 4 free nights, particularly at the low comparative cash price point. Maybe you’re happy enough getting 2 “free” nights and paying $200 for two additional nights. However, you have to imagine this difference at scale. If you don’t take into account long-term thinking about how these decisions scale, you will earn far less free travel than you otherwise could (and/or spend far more on travel than you need to spend).

Ultimately, the outcome is similar to the person shopping for a car based on the payment: you might get a result that makes you happy enough (driving the car you want for a monthly price you can afford), but the person who pays that price for 60 months is getting far less value in the long run and will have far less money in the long run than the person who pays that price for 36 months. By the same token, the person getting four or six free nights will have more money to save / invest / spend on other things by maximizing return on spend and use of points for good value.

Fractions of a cent help us make better long-term decisions

The same concept plays out over numerous examples in our hobby.

For example, shopping portal Rakuten offers the opportunity to choose whether to earn cash back or earn Amex Membership Rewards points. Which should you choose to earn — 10% cash back or 10 Membership Rewards points per dollar?

The answer there depends on how you will use the points or cash. Let’s imagine that you were going to spend $1,000 and you could either earn 10% cash back ($100) or 10 points per dollar (10,000 points). Fractions of a penny help us make a better decision as to which to earn (and when to use the points if we choose to earn points).

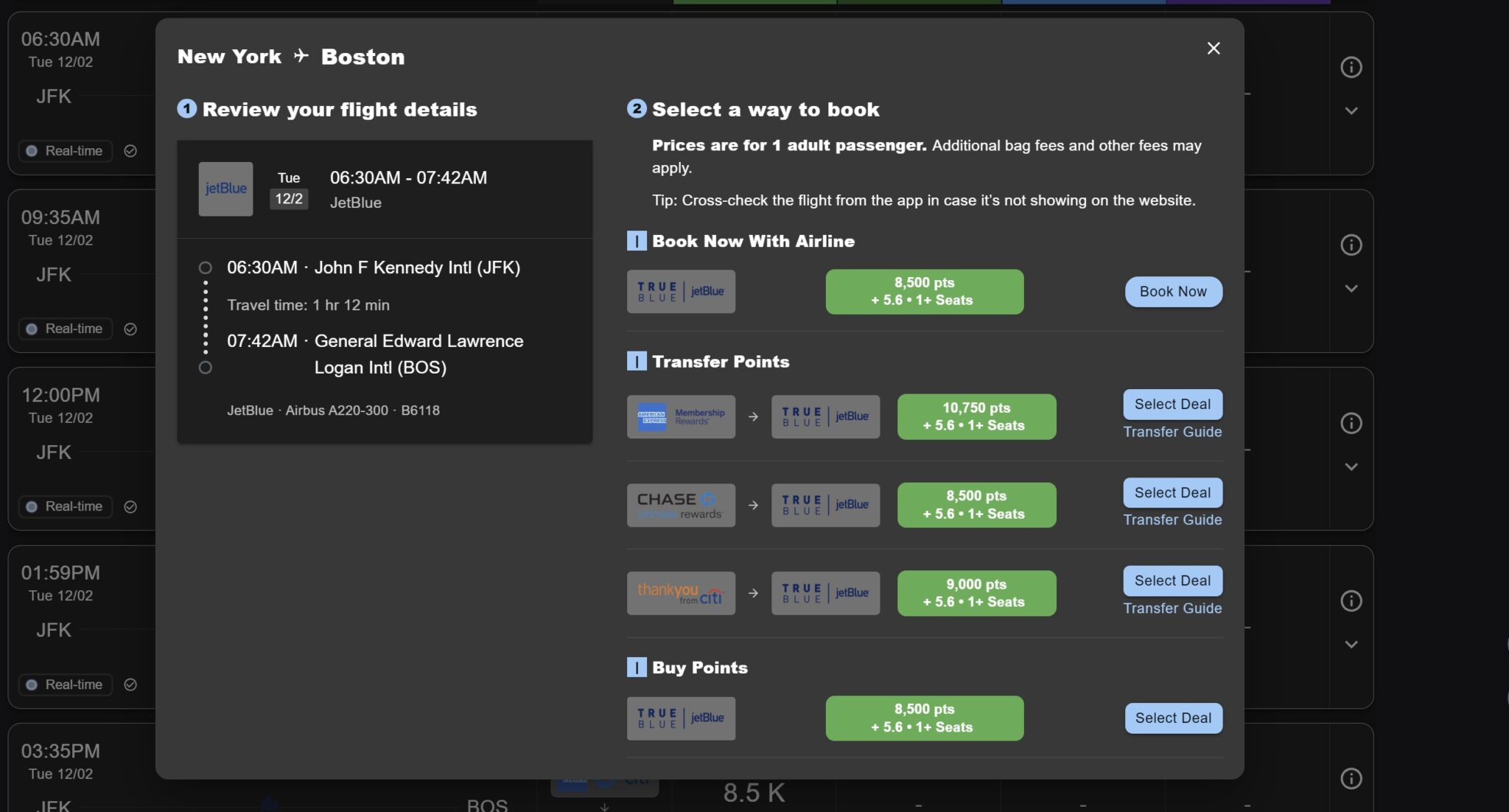

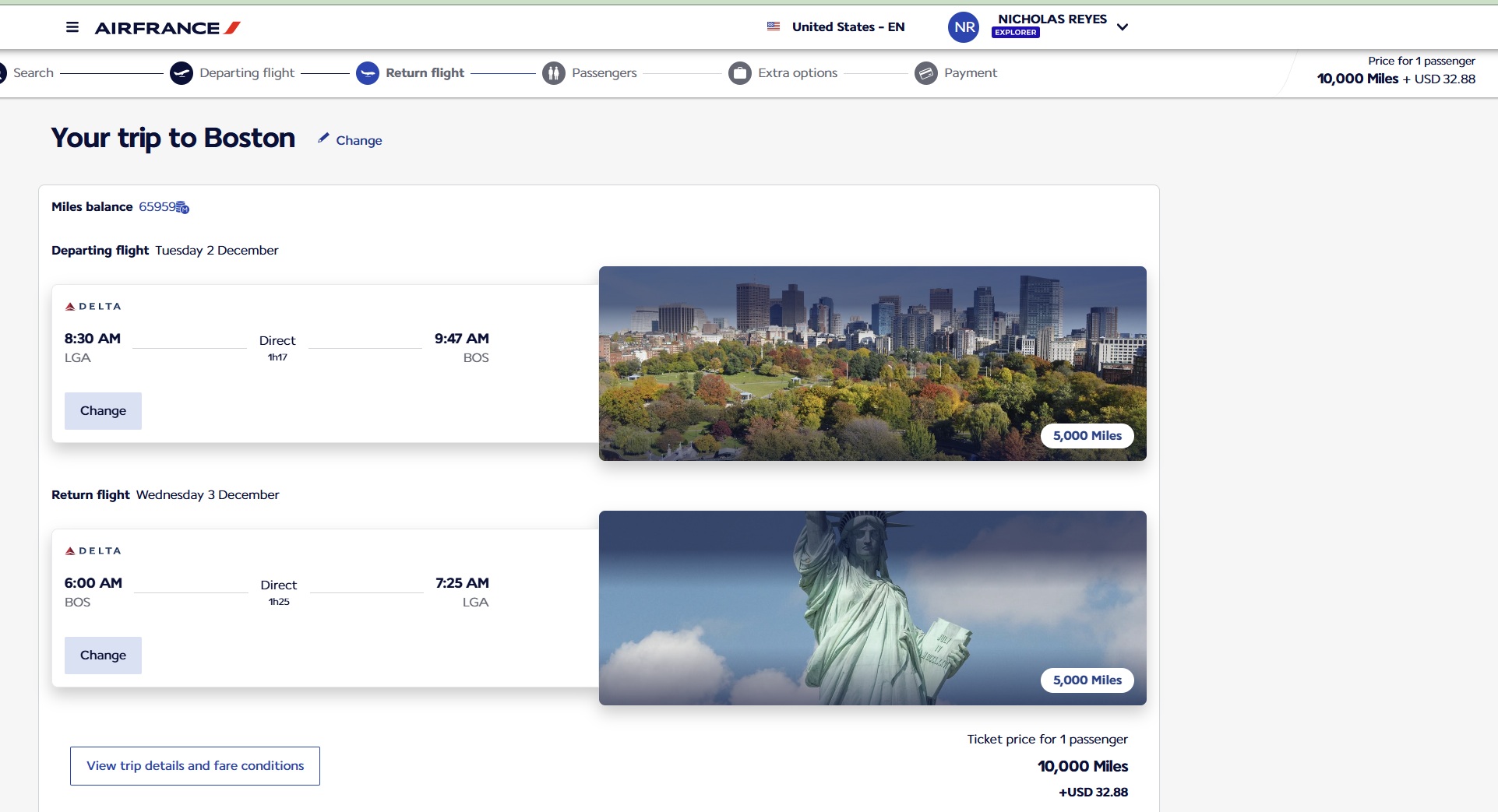

For instance, let’s say that you wanted to fly from New York to Boston on December 2nd (a new travel example).

That 10,000 Amex points wouldn’t be enough to get you a nonstop flight on JetBlue because of Amex’s transfer ratio to JetBlue. You would need 10,750 Amex points to get that route via JetBlue (and, oddly, Amex charges a fee to transfer to US-based airline programs, so you’d have to pay Amex for the transfer, and you’d need to transfer in increments of 1,000 points, so you’d really need 11,000 Amex points).

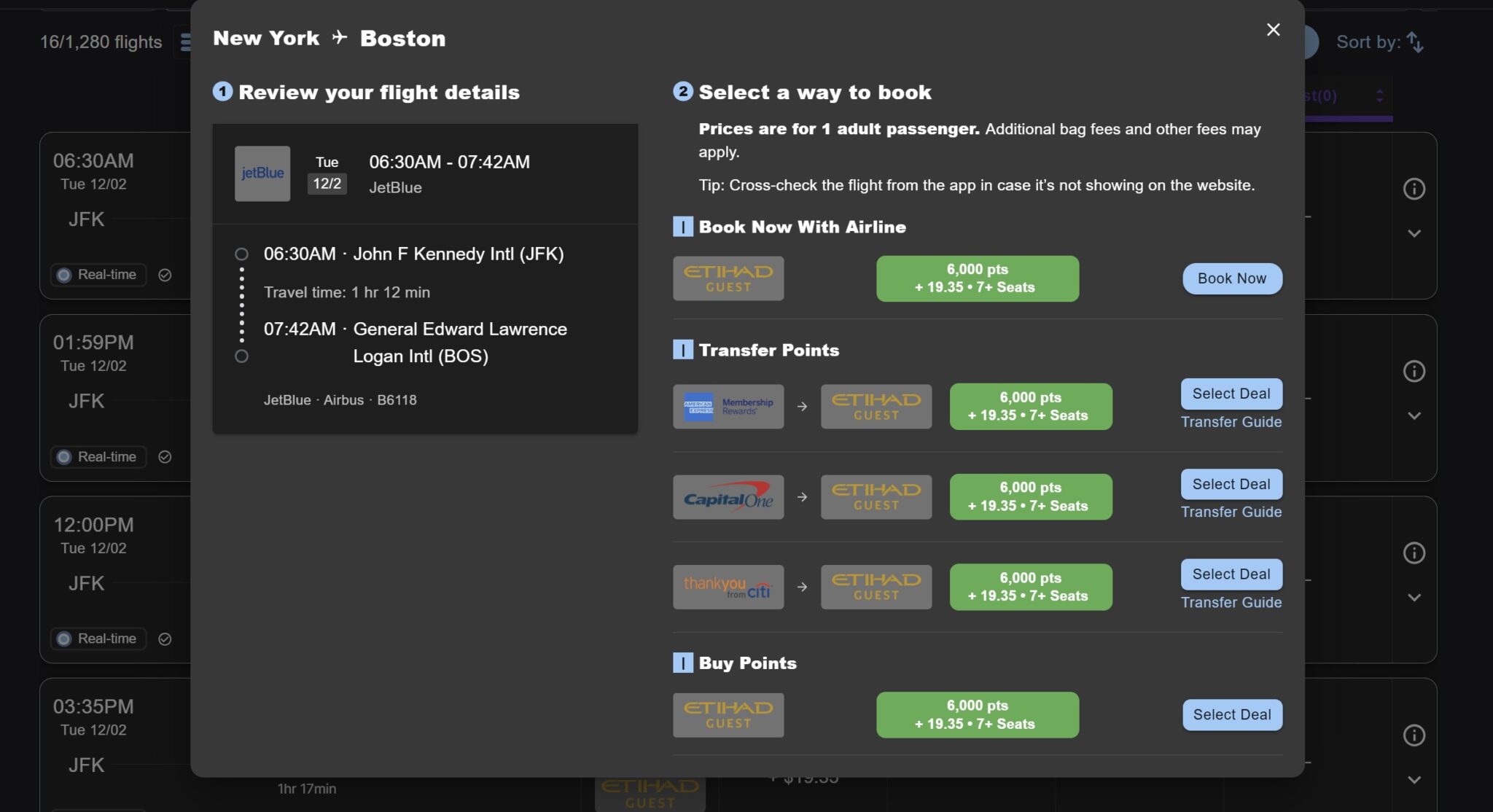

However, you could get that flight by transferring instead to Etihad Guest, which has it available for just 6,000 miles (and you wouldn’t pay a fee to transfer to Etihad, though you would have Etihad’s poor cancellation policy and slightly more in taxes & fees on the ticket).

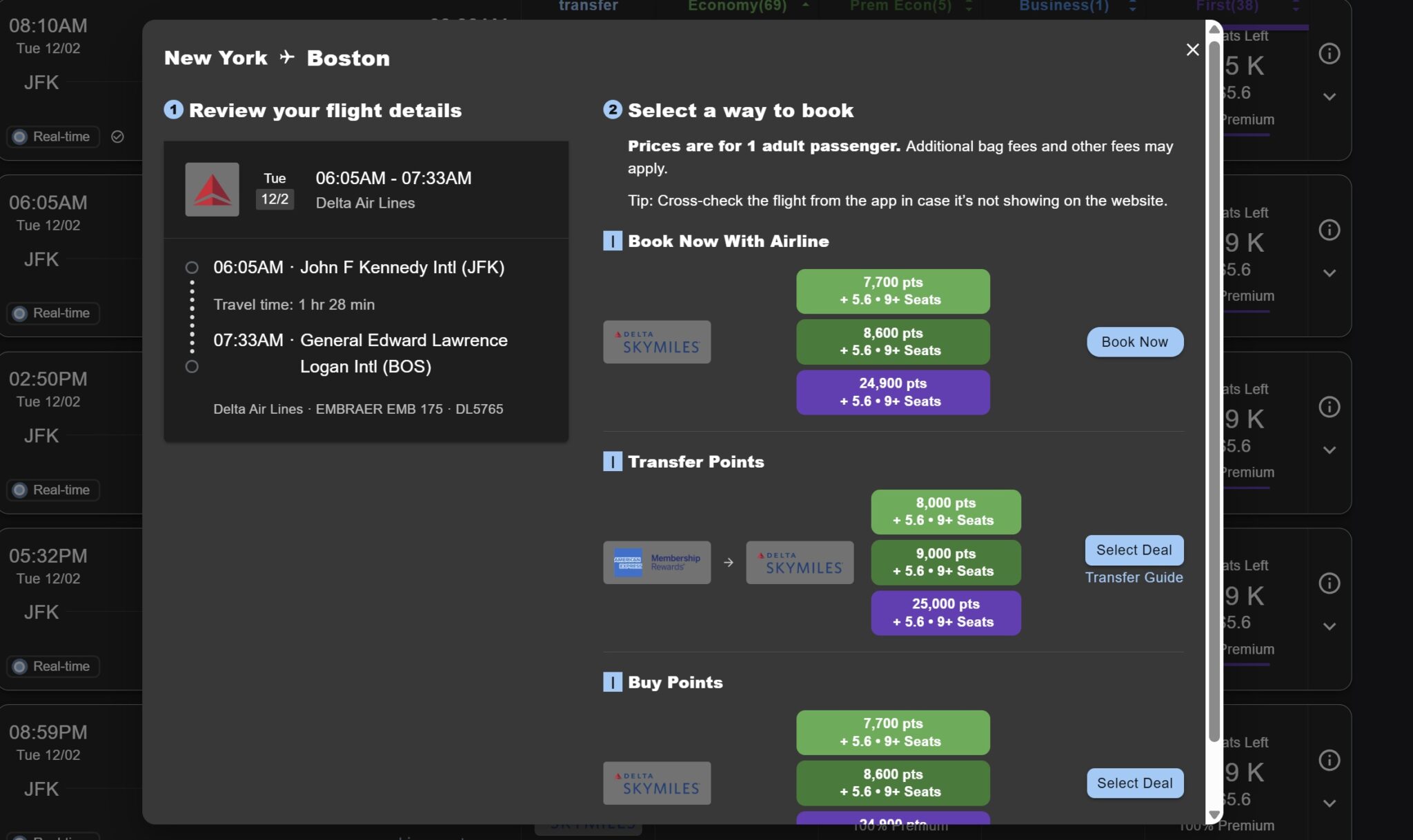

But maybe you don’t like Etihad’s cancellation policy and you’d rather fly with Delta. You could alternatively transfer to Delta and book that same route from 7,700 points one way (though, again, you’ll pay Amex a fee to transfer to a domestic program, and since you need to transfer in increments of 1,000, you would need to transfer 8,000 points to Delta).

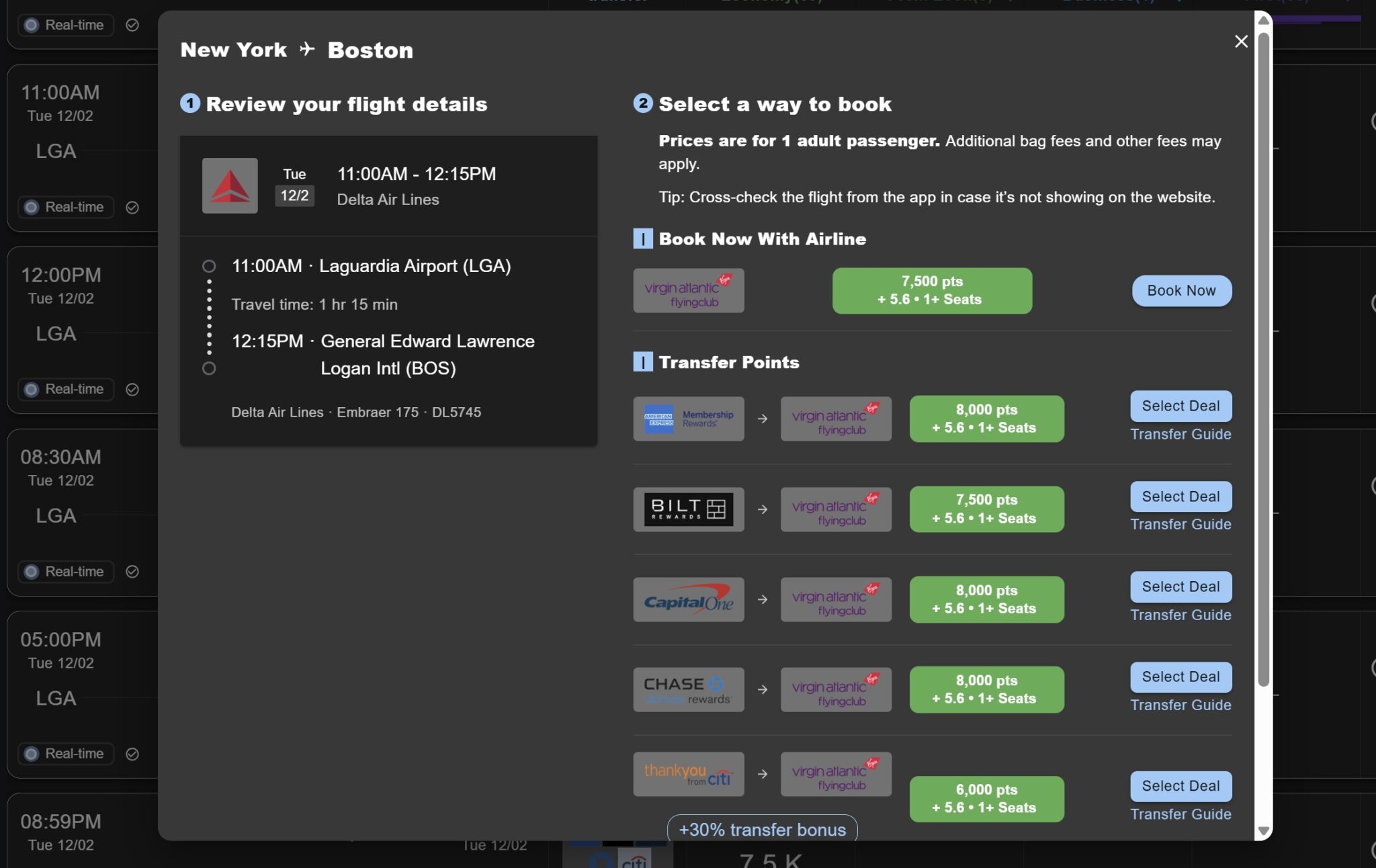

Or maybe you don’t care about the cancellation policy, but you don’t want to pay the Amex fee to transfer to Delta. You could alternatively transfer to Virgin Atlantic and pay 7,500 Virgin points one-way for the same route (again, transferring 8,000 points to Virgin Atlantic).

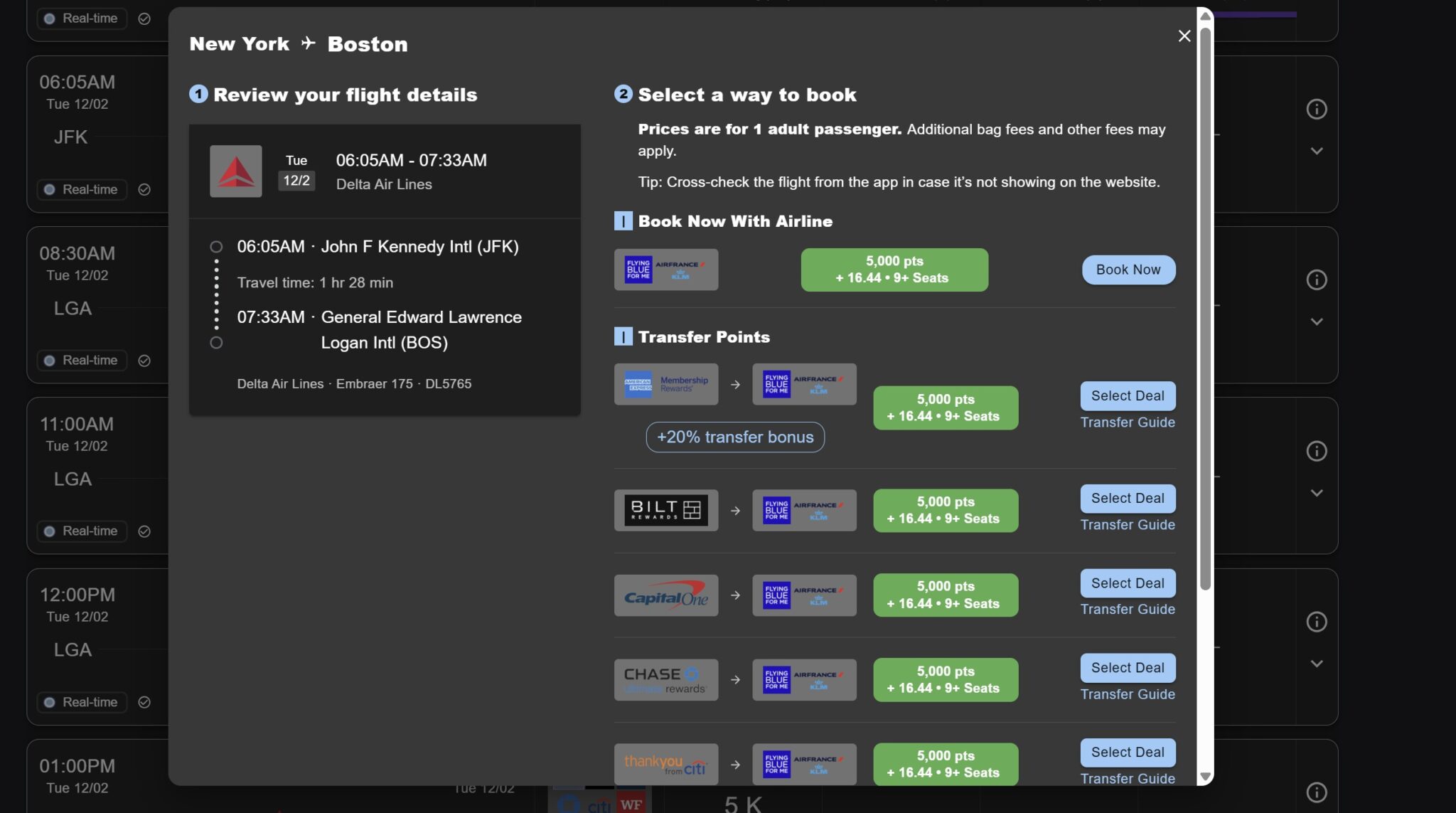

But you can do even better. The same flights are generally available via Air France / KLM Flying Blue, but you’ll pay just 5,000 points each way. With the same 10,000 Amex points, you could fly not just one-way but round-trip. And with the current 20% transfer bonus, you’d only need to use 9,000 Amex points to get 10,000 Air France / KLM Flying Blue miles.

But should you use points? That depends on the flight(s) you want to book.

One-way flights on the date I used above start at $64 for JetBlue flights or $69 for some of the Delta flights. Round-trip trips start around $127-$137, but they increase substantially depending on which flight or flights fit your needs.

If you redeemed your points for one of the cheapest one-way flights via JetBlue or Delta, you’d be getting a poor value for your points. After all, if you could have booked one of those for $69 or less, you would have been better off earning cash back through Rakuten. The $100 you would have earned in cash back would have been enough to buy the $69 Delta flight and have $31 still in your pocket.

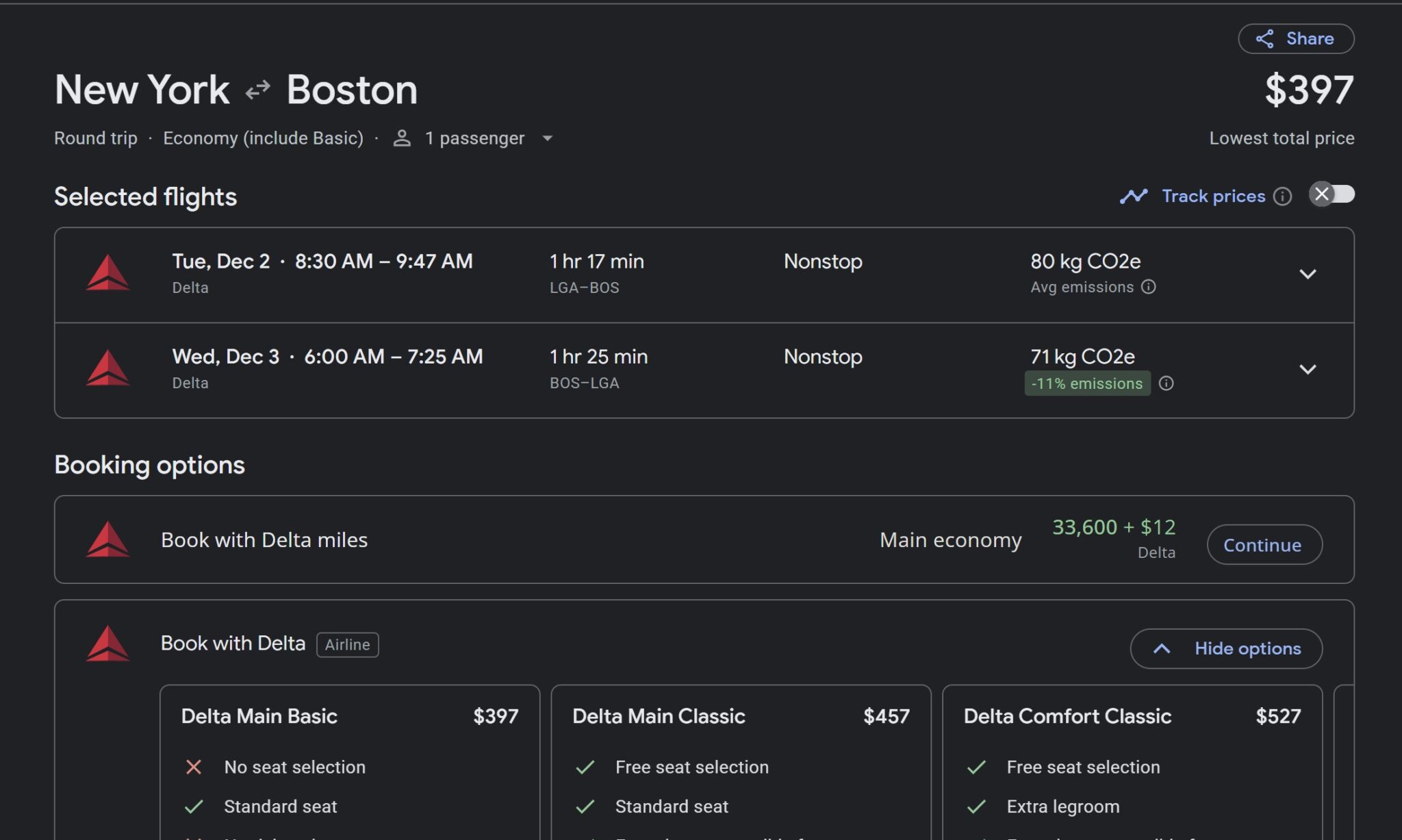

However, as you might expect, some flight times are more expensive than others. Take, for example, this round-trip combination from New York to Boston from December 2-3, which costs $397 in cash.

If you had chosen to earn $100 in cash back from Rakuten, you’d need to come out of pocket for an additional $297 to book that exact combination of flights.

If instead you earned Amex Membership Rewards points and transferred to Air France / KLM Flying Blue, you could book the same exact round trip for 10,000 points and $32.88.

With the current transfer bonus, you’d only need to transfer 9,000 Amex points to end up with more than 10,000 Air France miles and come out of pocket for $32.88. You’d end up with 1,000 points to use for a future trip and be far less out of pocket to book that round-trip combination.

That is admittedly a somewhat outsized example, although at the same time, it isn’t far off from the types of redemptions / decisions that we make regularly in this hobby. I’m not saying that I would intentionally choose a flight with an inflated price in order to get “better value”, but rather that I generally save my points for instances where they get me outsized value like that. After all, if I chose to earn 10,000 Amex Membership Rewards points instead of $100, I only want to use those points when they get me substantially more value than $100 would have gotten me (if I am going to redeem the points for subpar value, then choosing points over cash back was unwise).

This example helps illustrate why I care about fractions of a cent per point. If my initial choice were between an opportunity to earn 10,000 JetBlue points or 10,000 Delta miles or 10,000 Virgin Atlantic points or 10,000 Air France KLM Flying Blue miles or 10,000 Amex points, one of those would be more valuable in this situation. The most valuable would be Amex points, so that we would have the flexibility to choose the partner that best fits our need (and which might offer a transfer bonus to get more miles), so our Reasonable Redemption Value for Amex points takes that flexibility into consideration as compared to transfers to each individual partner. At the same time, it is important to have a comparative idea of the value of collecting 1 Air France mile versus 1 Virgin point versus 1 Delta mile so that you can make the best choice in terms of which to earn.

The same comparisons are important when we think about earning hotel points or other forms of airline miles. The math is incredibly important.

And that importance is magnified when my choice is to earn 1 airline mile per dollar spent versus 2% (or more) cash back. If I won’t use those airline miles to get substantially more than $0.02 per mile, then I should have chosen cash back. Digging into the weeds on value helps us decide which card to use in a given situation so that we can maximize our rewards.

The good news is that you don’t need to do all of the math

The good news here is that you don’t need to do all of the math. We do a lot of math to help reduce the workload for you!

For starters, we develop Reasonable Redemption Values for the various types of points you can earn, which can give you an idea of to comparative value and the chance to compare against your options for earning cash back for the same purchase.

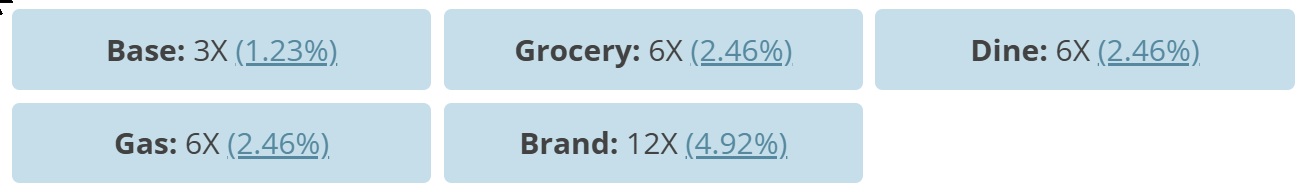

We further display category earn on various credit cards, both in terms of the number of points per dollar that they earn and the approximate relative rate of return based on the reasonable redemption value of the points.

Within each bank section of our Best Offers page, the offers are sorted by best first-year value. That isn’t based on a subjective analysis, but rather it takes into account the reasonable redemption value of the welcome offer, subtracts the cost of the annual fee, subtracts the opportunity cost of putting the spend required to earn the bonus on that card versus a good cash back card, and adds the value of certain easy-to-use and easy-to-value perks (like airline fee credits, which we automatically reduce from face value since you are prepaying for those benefits).

When we write about big spend bonuses, we examine the incremental value of whatever bonus you’ll receive and consider it in comparison to the additional spend required to determine how much it “costs” to spend toward that bonus. For instance, if you would spend $40,000 on an American Airlines credit card at 1x to earn 40,000 miles and American Airlines Gold status, you have to consider that you could have earned $800 cash back with the same spend on a 2% cash back card or $1,200 cash back on the Robinhood Gold card; are 40,000 miles and the benefits of AA Gold going to be worth more than $800 or $1,200, or should you have just earned cash back and paid for checked bags and a seat seleciton once or twice per year? If you redeemed those 40K miles for a single “free” flight this year, you might feel satisfied enough, but ten years of earning 40,000 miles and a free checked bag and seat selection that you use for a single round trip versus 10 years of earning $800-$1200 makes quite a difference in the long run. You might have been able to buy that flight, checked bag, and seat for $500 each year and made an extra $3,000 to $8,000 in cash back over the course of ten years. Maybe you’ll be happy with your “free” flight every year either way, but I’d rather have that flight each year plus an extra three to eight grand in my pocket ten years from now. Tenths of a cent matter to me.

At the same time, as a blogger, I want to be able to write about how the benefits of AA Gold work and how Loyalty Points boosts work on some AA cards so that I can help you decide whether it is worth spending $40,000 to pursue, so I personally make some choices that I wouldn’t make if I didn’t write about this stuff. Don’t base what you should do on what folks writing about this stuff choose to do. That won’t always make sense. Instead, take the experience we share to inform your own decisions.

Don’t let me steal your Joy of Free, but also consider cash back carefully

All that aside, Greg has written in the past about the Joy of Free. When we get into the weeds with the math, you could argue that we steal the Joy of Free. If you’d rather just enjoy your Joy of Free and ignore the overall numbers, that is obviously something you can do and be happy doing. Maybe you would rather dedicate mental bandwidth to something more meaningful to you than the maximum value you can eke out of your points. That isn’t wrong. As a miles and points blogger, it isn’t the path that I am going to advise since I am a numbers guy and I enjoy wringing tenths of a cent in value out of my points, but you may not want to dig into value with the same tenacity.

But here’s the thing: if you don’t enjoy chasing outsized value and crunching the numbers regarding the number of points per dollar you earn or how many cents per point you’re getting on the redemption end, cash back might be a better strategy. That is to say that you may end up with far more travel or far more money or both if you focus on earning 2-5% cash back on all of your purchases instead of focusing on airline miles and hotel points. I think a cash back strategy is a better choice for many people than a miles and points strategy. What makes airline miles and hotel points a potentially better strategic choice really and completely comes down to the math. If you hate the math, you are relatively likely to come out behind in collecting and using airline miles and hotel points.

But I (and most of us at Frequent Miler) love the math. I love being able to travel more and more comfortably than I ever would have imagined possible, thanks to our focus on miles and points strategy. I find joy in both the “free” travel and in the maximization of all aspects of it. So, yes, we do get lost in the weeds with the math from time to time. And I have no doubt that it is occasionally difficult to follow the numbers (particularly in podcast format). But I (and we) will surely continue to share the joy found within those numbers precisely because we find the opportunities to come out far ahead to hold some of the greatest excitement found in this hobby.

That doesn’t mean that you have to share our focus entirely. And it doesn’t mean that we don’t occasionally make poor choices with our miles and points. But if you want to “win” in this hobby in the long run, I strongly suggest embracing the math and working on the numbers because the keys to winning the game are hidden somewhere between tenths of a cent per point.

Im an engineer – and 10,000% agree with this post (which I also recognize is not how math works). However, this analysis also results in analysis by paralysis. Add in other intangibles like cancellation/change fees, status/perks, layovers, fare classes and hard/soft products – and things get far less black and white.

Example 1: Flight for spring break. Cash price on southwest is $100. $150 with a seat assignment, $200 for free cancellation. I have non-expiring southwest credits to burn. I also have some AMEX flight credits I could also consume. However, I can also get a flight for 8,500 AA miles, where im a platinum pro. AA seems like the logical option – but I have those credits to burn.

Example 2 – Looking for flights to return from Europe (already have outbound booked via AS – 45k business class, cancelable with $12 fee). Really want to go to Japan instead – but haven’t found Business Class flights that are reasonable – so I want to keep my options open. Best flight option back from EUR is 60k on AC…but their cancellation policy is terrible. So I booked 35k for a Premium economy flight with AS with full cancellation ($12) while I wait for a better option to materialize.

Point is – strict monetary analysis only get so far. Some of the other non-monetary variables plays a TON into my calculus…and often makes it hard to make a decision!

I love the depth of the analysis, which is why I’m a regular reader. Like everything, though, I think there is a spectrum, and getting too close to either end is not ideal. Points are a currency, and just like with any currency, there is a certain amount of math that you should do to make sure you are not wasting it. At the same time, you can go too far trying to get the absolute best value, to the point where the time and effort you put in yield diminishing returns.

I use Award Wallet’s “Look Up” tool to figure out which card to use sometimes. Wouldn’t it be great if Apple Pay and Google Pay integrate a similar tool into their wallet apps?

America Loves Math!

This is great. Would be incredible value to see more of your thought process on these kinds of things. Like “I want to go to location x and do y for z length of time” and then walk through your thought processes to optimize it.

Which award search tool is that you’re using, by the way?

Bob: do I really have to run a marathon or can I just run a couple of miles on weekends?

Nick: well, you can… But think about how many more calories you’ll burn and the strong calf muscles you can show off if you run a marathon!

2-mile run x 52 weekends = 104 miles.

(Assign your own cpm for those 104 miles).

For me getting the flight/hotel I want when I want it is more valuable than getting “outsized value.” Of course I’ll run through the options and book the cheapest one but I’m not wasting my time positioning or stopping over just to get a lie flat seat for 10cpp. I focus more on earning than burning. Gonna miss the CSR and USB AR 1.5 though

Well if that explanation didn’t put her off, nothing would!

You’re getting lots of well-deserved applause in the comments. At the same time, I feel like there was a missed opportunity here. Instead of taking the math all the way for the folks who already have their galoshes on to follow you into the weeds, perhaps this could have been an ideal post to woo the Bobs of the world with a straightforward example of how braving a bit of math yields a dopamine hit and a longer vacay. That’s how the post started. After your first analysis of getting 2 vs 4 nights at the SC Hyatt, though, the post feels like a bit of a turning away from the purported audience toward your usual fan base. I’m in that fan base, for sure. Just wished for a fuller perspective-take from you on this one!

I agree. This was WAY TOO LONG for a Bob and Jane of the general public.

I think a lot more tutorials would be very helpful. There are some very high level guides here on sweet spots, but they really could use a lot more details behind the thought process. And if you don’t have a decent knowledge of the best ways to use the points, it’s hard to really internalize why you might prefer points A over points B or cash on the earning side. You all are awesome but more coaching on the burn side would enable the earn side even more.

Here’s all the math I need to know: I want the most amount of travel possible for the least amount of points.

How do you know you’re accomplishing that?

Wow, Nick, just wow.

I really enjoyed this post, but I kind of felt like it missed the point that maybe Bob was trying to make in that this analysis that you just did is fairly complicated and took a great deal of time and for those of us who have very busy lives the element of time and complexity can feel overwhelming and sometimes it’s just better to take the easier route if you’re still getting travel for free that’s still a win, even if you’re not maximizing the value and sometimes the reduction in savings is worth the increase in available time. One has to remember to take into account the opportunity cost of time spent doing something.

Ok, I’ll take the bait and duke this one out as the Joy of Free Grinch for the sake of the skeptics! You didn’t ask for a fight, but I’ll push back.

I would argue that it’s not a blanket “win” any time you travel “for free”. If Bob used 40,000 Amex points for $280 worth of hotel that he got “for free” when he could have alternatively gotten $300 or $400 in cash back for the same amount of spend, the “free travel” cost him the chance for an extra $120-$220. Sure, he’ll have spent $280 less on that hotel than he would have without points, but he’ll be $120-$220 poorer than he could have been if he just earned cash back. Even if it takes him an hour to get the math, most people would find an hour of effort to be worth $120 to $220. And I would argue that as he gets used to doing that math, it won’t take him an hour for every trip he books, it’ll become more intuitive. And I would argue that the mental energy spent becoming comfortable with the math yields far more returns from this hobby in the long run than most things that people do in their free time. Some folks obviously have less free time than others, but I think that most could pour an hour or two a week into a hobby. Some will choose for that to be golf or pickleball (and one of these days, you’ll find me on the pickleball court, too) that have physical and mental health benefits, but I think that dedicating some of that mental bandwidth here yields outsized returns. We’ll each come to our own conclusions regarding how much mental energy each of our side pursuits is worth, but I certainly find this hobby to provide more upside than most I’ve ever had. Obviously, I have the bias of writing about this stuff for a living, so take that for what it’s worth to you.

That said, I will readily admit that I sometimes make make slightly suboptimal redemptions, the same as most other people in this hobby from time to time, but I think it’s important for your overall strategy to be rooted in doing the math or else the time and energy you’re spending collecting the points in the first place might be yielding you poorer results than if you just earned cash back. That isn’t to discourage anybody from collecting miles and points, but rather to recognize that there is time and effort involved *and that the juice is worth the squeeze* if you can dedicate the time to it.

Far be it from me to complain about the fact that some people make suboptimal redemptions. That’s partly what makes it possible to get highly outsized redemptions. But I do encourage readers to be the outliers where possible.

Side note that is unrelated to your point but relative to the overall discussion: I always find it fascinating when I come across people in my daily life who will drive out of their way to save $0.10 a gallon 14 gallons of gas two or three times a month, but then aren’t using a good gas credit card to fill up their tank! Stack those wins! And worry more about the bigger wins. That philosophy applies here as well – if you’ve got the time to either spend an hour chasing a $1,000 win or a $120 win (all else being equal), obviously you should put the effort into the $1,000 win as being the mathematically superior choice and go ahead and redeem those points at suboptimal value. But I think a lot of people have the opportunity to do both!

A very very long blog post about cutting down on the overthinking…..what has worked for my family is continuously getting P1/P2 new card signup bonuses with achievable required spend cards. Get enough points to take all 4 of us in economy class with nice hotels/resorts 2-3 times per year with little cost. Keep doing this, don’t wait for trips because it will cost more next year. Don’t not take a trip you want because it doesn’t max your cents per point, just be generally aware of what points can be worth because 100,000 airline miles for a $500 flight is a bad trade.

Great piece but I think the last section is the most important for bob and others like him: if you don’t want to do math, odds are cash back is much better for you

If you want to travel frequently or at a higher level of luxury, then you probably work harder and strategize to amass the points needed to do so. If you are working at something, then the reasons to do the math become much more obvious since your hard work will go much farther. As is often said, the fact that most people are unwilling to do the math is the reason the rest of us do so well in the hobby.

If you travel infrequently, then getting what you need is much easier and I can see how doing the math is less important.