Earlier this week I conducted new analyses and published new Reasonable Redemption Values for AA, Delta, and United miles. The terribly poor results, particularly for AA and United, forced a bit of a crisis in my mind regarding how we at Frequent Miler value points. Is it time for a change?

At Frequent Miler, our paradigm for valuing points and miles has long been referred to as “Reasonable Redemption Values” AKA “RRVs.” The idea started with this concept: it’s impossible to give points and miles a fixed “value” in advance because the value you get depends entirely upon how you use your points. For example, you can redeem American Airlines miles for about one cent per point value towards domestic flights, or you can (sometimes) redeem those same miles for over three cents per point value towards international business class. On the other hand, we pride ourselves in providing unbiased information to our readers and a key part of that is to display credit card offers sorted by estimated first year value. When an offer includes bonus points or miles, we need to assign a fixed number to the value of those points so that we can show people the value they are likely to get. So, we developed Reasonable Redemption Values: values with which you can easily get that much value, or more, even if you don’t try hard to cherry-pick the best value rewards.

Our 2019 “Fix”

Since developing our Reasonable Redemption Values, we expanded our use of these values to show how much value you’ll get from credit card spend. Some posts rely entirely on this idea. Two popular examples are: Best value for everyday spend, and Best category bonuses: Which card to use where?. By expanding our use of RRVs in this way, we were using them in a way that was not originally intended. By showing a credit card’s earnings for spend in terms of RRVs, we were implicitly saying that our RRVs indicated the cash-equivalent value of points. That was a problem because RRVs were never meant to be cash-equivalent values. RRVs (as originally conceived) should be higher than cash equivalent values. Once we recognized this issue, we put a Band-Aid on the problem by selectively lowering certain RRVs to the point that they became reasonable to use as cash-equivalents. See this post for a full explanation: A big change to Frequent Miler’s point values.

The 25K round-trip problem

Our RRVs have been long out-of-date, especially for airline miles. The original simplifying idea behind our airline RRVs was this:

- Most airline miles, at the time, allowed booking a round-trip domestic economy U.S. flight for 25,000 miles.

- Most real-world award redemptions were for domestic economy flights

- We could look up average domestic flight prices

- We then calculated RRVs as the average cash price* divided by 25,000 miles.

* We accounted for TSA fees charged to award tickets by subtracting that amount from the average cash price. Later, we also accounted for the lack of earned miles on paid flights by adjusting the RRV downward by 7%.

After developing that methodology, airline miles changed. First Delta abandoned award charts and then, later, United did the same. And even though AA still has award charts, they also have Web Special Awards that are priced however AA wants to price them. In other words, with few exceptions, the idea of the 25K round-trip domestic award is long gone.

New process

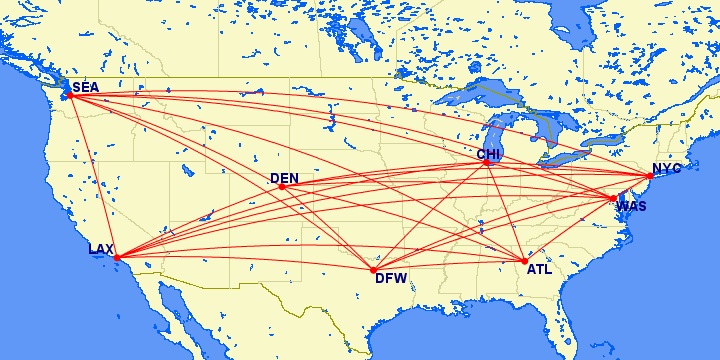

In keeping with the idea that most people in the U.S. redeem their miles for domestic awards, I developed a process to estimate the value of miles when used that way. Full details can be found in any of these posts where I explained our new RRVs: AA, Delta, or United. The short answer is that I picked a future date and ran cash and award searches for one-way flights to connect all of the popular airports (or metro areas) in this graphic:

The results were surprising:

| AA | Delta | United | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median CPM | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Minimum CPM | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.6 |

| Maximum CPM | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.2 |

Delta proved to offer the best value towards domestic flights (1.2 cents per mile, on average) whereas AA offered the worst (1 cent per mile, on average).

It’s crazy to see Delta showing better stats than AA when we know that Delta charges far more for international business class awards. For example, AA charges as few as 115K miles for round-trip business class to Europe, United charges as few as 120K miles, and Delta charges a whopping 210K miles. But this analysis looked only at domestic economy flights and so that type of comparison is missed.

I’m confident that AA performed badly partly because cash prices are currently lower than usual. AA’s award prices are much less tied to the cash price than are Delta and United’s. As a result, I believe that AA’s domestic cents per mile value will increase when cash prices increase. In fact, I bet that simply by picking a different date or origin and destination combo, it would be easy to find better AA values right now. My intent is to update the above numbers regularly and so I expect that we’ll see AA do better in future analyses.

These new numbers have created a bit of a crisis in my mind regarding the point values we publish. I believe that the new numbers are as good as any (and better than most) for explaining the value you’ll likely get when redeeming miles for domestic economy flights. I’m having a hard time accepting, though, that these numbers represent the cash equivalent value of these points. With AA, especially, miles are worth so much more for international business class flights that a cash equivalent value of 1.0 just seems wrong. The values do accurately represent a “reasonable redemption value” in the original sense we meant it (it is reasonable to expect to get that much value or more), but as I pointed out earlier in this post, we no longer use RRVs in that way alone.

To err is human (and required)

How much are airline miles worth? There is absolutely no single right answer. Any number we publish will be wrong. In actual use, you will get better or worse value. And whatever value you get will be different than the value your neighbor gets.

I’ve always preferred to err on the low side. People use the information in this blog to decide which credit card to get, which card to put spend on, which portals to use, and whether or not it’s worth buying miles when they are on sale. I’ve always hated the idea that people will make financial decisions like these based on overenthusiastic point valuations. Yes, you can average 2 cents per mile value, but will you? For many advanced readers, the answer is probably yes (at least for some types of miles). But I believe that the majority of readers, especially those who need our advice about which cards to get and use, are fairly novice when it comes to award booking. Most readers probably use the majority of their miles towards low value domestic flights with only an occasional high value win now and then.

Erroring too low is a problem too. As things stand right now, I believe that the AA and United RRVs are too low. Readers without more information will gather from our blog that it is better to earn Delta miles than AA or United miles. But that’s only true if their goal is to fly Delta domestic economy (and even then, they’d probably be better off with cash back cards, but that’s another story). If the goal is a dream international business or first class trip, they’d be much better off with AA or United (and even better off with transferable points, but again that’s another story).

Is it time for a new approach?

Given that this blog uses point values to indicate cash-equivalent value (even if that wasn’t our original intent), I believe it’s time to take a step back. Is there a better way to calculate cash-equivalent values than by calculating the median observed domestic award value?

My current thought is to continue to assume that most awards are domestic economy, but to also acknowledge that some are likely to be international business class. If we can estimate international business class values for each airline program, we can then create a blended RRV that is something like 70% domestic economy and 30% international business class. I wrote “something like 70%…” because I want to reserve the right to futz with the numbers so that the final answer meets the sniff test.

I’m imagining taking a subset of the original domestic U.S. airports and calculating CPM (cents per mile) for international business class from each of those cities to a set of international cities:

Using the data from such a project, it should then be possible to publish three point values for each mileage program:

- Domestic Economy RRV

- International Business RRV

- Blended RRV (this will be the number used for displaying credit card reward values)

The Blended RRV would be the cash-equivalent valuation. This would be the number to use when making decisions about acquiring new points through credit card spend, buying points, choosing a shopping portal, etc. The domestic economy RRV would be mainly there to inform those who intend to use their miles this way. If you’ll be booking domestic economy awards, your goal should be to get better value than the domestic economy RRV. And the international business RRV can be thought of as a target for cherry-picking awards. For example, if you’re trying to figure out if an award is a good deal, you could compare the point value for that redemption against the international business RRV. If your award is as good or better, then it’s a great deal.

Conclusion

In my opinion, the current approach of valuing airline miles based on median domestic economy awards is no longer a good solution. While it continues to avoid overvaluing miles, it has gone too far towards undervaluing them. In this post I proposed a solution: we could estimate both domestic economy mile values and international business class values. We would present both on the blog and create a composite score for situations where a single number is needed (such as in our credit card displays).

Once we’ve figured out how to do this “right” for AA, Delta, and United, we’ll expand the approach to cover miles in other programs (Air Canada, Air France, ANA, British Airways, Virgin Atlantic, etc.).

Reader Input

I’d like to hear from you about the above proposed changes. Is the idea good or bad? Do you have a better idea for how to tackle this? Please keep in mind that I’m not looking for a perfect solution: I don’t believe that such a thing exists. And I’m not looking for a solution that will take a lot of investment. I want a fairly simple solution that is better than what we have right now.

What do you think? Please comment below.

![Hyatt goes next level with Mr & Mrs Smith [Integration “early 2024”!] a heart shaped sign over a house overlooking a body of water](https://frequentmiler.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Mr-and-Mrs-Smith-and-Hyatt-218x150.jpg)

Thanks for this super thoughtful post, and for being transparent with readers about your thinking. I’d prefer a blended value that does not incorporate the cash price for international business class tickets. Several others have made this point, but I’d simply never pay the premium cabin price for ANA to Tokyo, for example, even though my end goal is booking business/first with points and miles. I’d suggest including domestic economy, domestic first and international economy in blended value.

Greg, I’m pretty sure nobody is going to care about this “accounting lesson” but as a longtime reader of your blog, I thought I’d share a few thoughts in case they are helpful to you. I teach accounting at a large state school. It occurred to me today that one of the reasons I like your blog so much is that you follow a lot of the principles that I think represent good accounting standards. The purpose of financial reports is to provide information that is useful to people for making decisions. There has always been tension in accounting standards between providing information that is reliable/verifiable and information that is relevant to users. Obviously, information about an upcoming product release might be really important to investors in Apple or Tesla stock, but until there are actual sales, expenses, etc., related to these new products, financial information about such new products generally will not find their way into a company’s financial statements. These principles are reflected clearly in what you describe as your approach to coming up with reasonable redemption values.

There is a third accounting principle that I teach my students as well: conservatism. The idea is that financial statement users are likely to be worse off if you overstate assets and income (because they will overpay for the stock and lose money when it becomes clear that the company is not as good as it appeared to be) than if you understate them (underpaying for the stock generally doesn’t upset people, although obviously if they decide not to invest based on understated numbers they may later regret missing out of a good investment which is also a bad outcome). The goal is not always to understate assets and income, but given the tension between providing information that is both relevant and reliable, accounting standards usually opt for values that can be for readily verified and that are conservative (e.g., if an asset falls sufficiently in value, you immediately record a loss whereas if an asset increases in value, you generally wait to record the gain until you actually sell the asset). Everyone who understands accounting reports understands this inherent bias and can make adjustments to reported values as they see fit. Importantly, though, those who are new to reading accounting reports won’t pay too much for the shares of a company because assets and income are overstated (unless, of course, the company is trending on Reddit). That’s at least the idea (cue the jokes about crooked accountants and cooking the books).

You can do with these principles what you want, but I think they could be useful ways to think about RRVs. Those who are comfortable with the game can make whatever adjustments they see fit knowing how they will actually use the miles. Everyone who has been in the game for any amount of time knows the way to get big value from their points is usually to fly in the front of the plane over the ocean and to stay at fancy resorts that are on their own island. However, for those who are new to the game, for whom your RRV values are probably most helpful, I think your current conservative approach is a very good one. Seeing inflated valuations, even if they are reasonably possible to get for someone who knows the game, is a good way to get people to make emotional rather than rational decisions. I don’t think that is your aim with this blog, which may be the biggest reason why I have followed your blog for a long time while most other blogs (with the exception of DOC) in the points and miles space rarely keep my attention for very long.

Thanks! I enjoyed this comparison to accounting lessons!

Miles can also get more valuable if you have a bit of diversification in your portfolio.

Supposed you had only Delta miles and did a blend of domestic and international travel. You would get good value domestically and poor value internationally. If you also have American miles, however, you can keep using Delta domestically and switch to American internationally and get solid value across the board.

Obviously you need a critical balance in each program, but if someone has, say 200K miles in one program, the next most valuable miles to collect might be whatever they don’t have.

I’ve been collecting miles for a long time, and I almost always use them to pay for flights that I would have purchased anyway. I think the vast majority of people are similar to me in that regard. IMO having too much weight on international business class redemptions overvalues the miles vastly because I never pay money for that ticket. I’d rather go on twice as many economy trips or bring along friends and family.

on the podcast, you talked about comparing the award prices to the money prices on the same flight. That seems like a problem for people like me. If I am looking to fly someplace, and shop around across airlines with some parameters for not wanting to get to the airport at 3 AM or have too many connections or ridiculous layovers. If I want to fly to Rome for two weeks in June, I don’t care whether my connection is in ATL, MIA, BOS, or whatever as long as the journey times are fairly similar.

anyway, no system will be perfect for everybody. You’re not calling them perfect redemption values; they are just reasonable.

For me, international business is not a good marker either. Those flights can be expensive, well beyond what I would pay. When I value things myself, I just use a multiplier on the international economy fare. That multiplier, for me, is 1.5 or 2 maximum.

I’d suggest making your RRVs on international economy and let people figure the rest out for themselves.

For example, if I can get to Manila for $1000 cash and I use points to get there, I treat it as if it was a $1500 fare and use that as the value. Maybe the actual price would be $5000, but that doesn’t matter. I want to get to Manila. $1000 is the price to get to Manila and I’m willing to pay another $500 to get there comfortably, not an extra $4000.

Same applies to hotels. If $100 is the price to stay at an acceptable, for me, hotel, I’m not jazzed if I can pay oodles of points for the super-luxe experience since I’d never pay that in the first place.

Of course, all of this is very personal.

This is largely my way of thinking. I value international premium seats as some markup on the economy fare both for the comfort and the novelty.

For the same reason, Greg’s new valuation method would match my own thinking more closely if he compared the points cost on (say) Delta with the paid fare on the cheapest carrier on the route he’s looking at. Just because I’d get a good points value on a Delta flight doesn’t mean I wouldn’t have taken the United flight if it was cheaper (by enough).

I initially made the argument with Greg that we should do what you’re suggesting and compare to the cheapest option on the route. But what if that’s Spirit? I’d fly Spirit, but I know people who wouldn’t. I also know people who like Delta enough more than AA or UA to pay more for that product (and for a couple of years there pre-pandemic, AA was having so many issues and was so frequently late/behind schedule that I at least partially understood why people might pay more for a flight that they felt more confident would run as scheduled). In an international business class situation, I would absolutely be willing to pay more to fly Singapore or Qatar business than United business. The fact is that the products are different and while Delta might be more expensive than AA or United, they wouldn’t be priced the way they are if people weren’t actively choosing to pay more for their product. So then I figured that I guess it actually does make some sense to value Delta miles based on their value toward the product in question. I guess the problem here is that you and I might be looking at different products — I might be looking at the product being a “Delta flight” and you’re looking at it as “transportation to Dallas”.

With transportation I think maybe it’s easier to forget that there is actually a product there and just like in almost any other industry, there are multiple different products that someone might choose for one of many reasons. I bought a phone case yesterday. I saw one that would probably do the trick for $9 but I bought one that I liked more for $11. Is the case I bought only worth $9? Not to me — to me, it was worth paying a bit more for the one I liked better. I don’t think it would be accurate to say that I only got nine dollars worth of value for my eleven dollars. I got an eleven dollar product. It serves the same practical function, but it was item I wanted for whatever reason. The same type of logic could be used to think of a Toyota vs a BMW vs a Tesla or a Casio vs a Rolex or whatever else.

So the more I thought about it, the more it made sense to me to value the currency based on the product it buys and in a flawed world without a perfect answer, I think it makes sense to look at the product you can purchase with Delta miles to be a Delta flight since those miles couldn’t buy the Spirit flight even if that’s what you wanted (and you clearly didn’t want the Spirit flight or else you’d have gotten the Spirit credit card instead).

I do recognize your perspective though and shared it for at least some of this conversation this week.

Always impressed to see the amount of thought you guys put into this kind of analysis.

If using commodity domestic economy fares I think it would be reasonable to exclude some airlines from consideration. I’d do that mostly based on number of flights (to avoid getting stuck without a backup flight) but that would have the effect of removing Spirit, Allegiant, and others from most routes.

The consideration of whether domestic economy on one airline is “worth” more than another is difficult. You could adjust the valuations for exactly that factor using values that you decide, or that you take from someone who rates airline quality (or, you could develop a separate model yourself to rate quality!). But I’m not sure that would capture the nuance of airline preference, which is going to be based on individual factors like elite status

+1 happy to see you’re looking to evaluate values based on international business class flights. Ultimately it seems it would make sense to track at least 4 values to cover most options for economy/business and domestic/international.

One question regarding valuation: do you guys take into consideration award tickets that have terrible itineraries, e.g. an overnight stopover on a domestic flight? I don’t know how much that’s happening now, but I know in the past it’s been a problem I’ve experienced with the big 3, and a big reason why in the past I decided to forget trying to accrue airline miles: the decently-priced award itineraries were ridiculous compared to just buying a cash ticket (not necessarily with the same airline)

Yes, if you read any of the new posts about AA, Delta, or United values for domestic flights, you’ll see that I setup a made-up scenario where the person flying didn’t want too early of a flight and yet still wanted to arrive by 5:30pm, and no more than 1 connection, and no extremely long layovers. All of the results were based on that scenario.

Such a complicated calculation.

I like the point made about Turkish and simplicity. Cashback cards are straightforward. Using cashlike points such as Southwest is similar. A point is pretty much cash, takes seconds to use, and is guaranteed at 78 per dollar against the base fare if there is a seat available. And I can cancel for free virtually up to takeoff and points never expire.

If I want to get decent value out of some points/miles I could name, how many hours and how many searches will I have to do? Is it online? Must I call? How many failures and restrictions will there be? Can I cancel? What is the fee if so? What about expiration? Is there EVER availability on the route I want?

For me these frustration factors as I get older, though certainly hard to estimate, definitely play a large role.

And then there is the personal factor of what airport you use. To someone in North Dakota, how much is a Southwest point worth? Or a Companion Pass to him or to a single person anywhere who travels alone? But to someone in DAL, maybe thousands. A surprising number of newbies I have met plunge in and grab points/miles based on supposed values someone told them and then they cannot use them.

Pretty hard to boil everything down to one number with all these considerations.

I’m in the “international business/first class only” camp with my point usage, as domestic cpm is so dismal. Looking at your proposed routing for the international component, I only see London in Europe. As you know, London is problematic due to the high fee structure, and the insanity passed along on award tickets by some carriers (*cough* BA *cough*). So you’ll need to factor that in somehow. London being so popular, it probably deserves to be in the mix, but you may want to add some other destination in Europe that’s less problematic.

Greg:

From my viewpoint, FM has been undervaluing RRV for a few years. I understand your thinking and approach, but my individual situation (where I’m in “the game” for bucket list dream vacations – most often international) skews my personal valuations northwards of yours.

I therefore agree that your latest iteration of adjustments have gone too far where airline miles are being minimally valued based on omitting consideration of premium international award flights. I therefore agree with your proposed remedy, but will still consider your resulting RRVs as still a low ball for my purposes.

I must confess, however, that I find that it’s not a great use of my time to calculate my own unique RRVs. My approach therefore has been to average the main travel bloggers’ mile/point valuations to derive a number that I use when trying to value alternative strategies.

In doing this, I’ve noticed that FM already (before your latest changes) offered some of the lowest valuations. Therefore, I again agree (from this perspective) that your latest approach just simply feels like you are taking an already low ball calculation and making it even lower. That, in itself, suggests the need for adjustments.

This leads me to a suggestion – perhaps you should rely a bit less on your own “gut feel” on final results and instead compare your numbers to what others have calculated (if you don’t do so already).

The responses here are all over the place, probably because we all live in different places, travel to different places, and have different priorities on how we use our miles. Do we already have a trip planned, and we want to make it cheaper? Or more comfortable? Or maybe we want a “you only live once” trip?

Personally, I am fine with the RRVs you have been doing, and understand why you want to have them. I am guessing that many of the readers here, like myself, have already formulated their own RRV for the major three US programs. For me, it is definitely DL>AA>>UA, but I totally understand why it is not the case for most people. As several comments here point out, the true CPM is based on what we would actually pay, which is subjective. I personally find your site most useful when discussing the programs that I am less familiar with.

So for my vote, I do appreciate the domestic economy RRV approach, because it at least creates a floor value.

I think your last sentence nailed the goal here: a reasonable floor value. The problem is that our rubric for the floor value – domestic economy redemptions – is no longer reasonable.

An example I give on tomorrow’s podcast is an American Airlines credit card with a 60K mile bonus. Based on Greg’s new AA value this week, that bonus would be worth $600. But is that true? If someone who isn’t deep in the game comes to our site (and let’s be clear: there are a lot of people in that camp who do) and he or she wants to travel to Asia, do I want them to see the American Airlines bonus and think that a card offering a $600 cash back bonus is an equal option? Six hundred bucks might not get you halfway to Asia from many US cities but yet it could get you there in business class (albeit one way) with American Airlines miles.

And that’s to say nothing about whether we would buy AA miles at a price of 1c each. Manufactured spending aside, I think that most would agree that buying AA miles for 1c each would be a great deal for a large number of redemptions.

So while I like erring on the side of being conservative and I don’t think it is genuine or realistic to value an American Airlines mile based on the price of Cathay business class to Asia, I think the 1c valuation is too far flawed to accept. We could just create a totally subjective number that we pull out of a hat, but I / we like that our RRVs have long differentiated us from blogs who do that. I also the fact that the way we’ve done it has completely eliminated any question about the airline numbers being influenced by affiliate relationships. We obviously can’t keep our current methodology though long-term because the 25K round trip no longer exists. I’m still hopeful for a “scientific” sort of value. I think we all agree that’s not easy, which is what makes this conversation interesting.

With the domestic economy and international business class values being so far apart from each other for these 3 airlines, and the two types of travel (domestic econ vs int’l biz) being so different from each other, I agree with the sentiment there these two values shouldn’t be blended.

Instead, I respectfully propose that there be two different ways to sort the credit card first year values. They could either be sorted for a traveler looking for domestic economy redemption, or a traveler looking for international business class redemption. I think that would be much more useful than a hybrid value which would be less applicable for many people. If somebody wanted a combination, they could figure it out for their own situation starting with your published values.

I think the segmentation approach is exactly right. One single “blended” Cents per Point really doesn’t address ANY single customer segment so it never made any sense to me and I paid little attention to these estimates.

In our case, we use our miles almost exclusively for international business class and have had Cents per Mile returns of up to 10 cents per point. Even within that class there are multiple segments, e.g., international business class to Europe; to the Far East; to South America etc. I think identifying a handful of the most important segments (say by passenger count) and focusing on them is the “tasteful compromise” way to go. And I think what you lay out above is a good step in that direction.

As for estimating value amid fluctuating prices, how about taking a rolling annual average for a sample fo flights within each segment. That would help smooth out/adjust for price changes and seasonal effects.

My 2c = <0.015$ at most for any mile, usually less

I think no airline mile should be listed at more than the minimum value it has been on sale for the past 2-3 years. = 1.7c max for most miles

One should also consider opportunity cost of the miles. If an Amex point can be redeemed for cash at 1.25c; that is the usual cash value for a DL mile.

Yes, you can get a mileage award going through 3 stops and 48 hrs to get to Greece, but the value of same business seat paying cash is much more counting time and effort. So when calculating business award redemptions, factor this in too and discount the calculated value of a mile by 25-50%

Ultimate Rewards – Best redemptions are Hyatt for hotels and United / SW for airlines. Cash back only for travel is 1.5c with the Sapphire Reserve – no airline mile that can be transferred from UR is worth more than that usually

Most blogs have a built in incentive to maximize value of miles; so to be truthful you have to discount that too.

In general – a conservative value of 1c is true for most airline points; 1.25c is a reasonable compromise for most programs if you want to sell eyeballs.

However using the cards without bonus categories or after sign up bonuses will lose most people money in each transaction given the Citi cash back and BofA

Using just those – the lost cash value is at least 1.5-2c

As an avid reader of Frequent Miler, I don’t use the evaluation at all and don’t look at 1st year value, because 1) AMEX cards you can’t get bonus again or at least for 7 years, 2) chase sapphire 48 months 3) citi 24 months. And 4) chase 5/24 rule. etc.. the rules really dictates how I value the cards..so as said before in a post most of us aren’t beginners and have to navigate what cards we are even able to get… I also see your home airport as a critical component, I.e. I’m not in Atlanta, Detroit, LA, etc, so Orlando valuation really means to me which airlines I can get the best deals from.

to be clear, I love your analysis, articles and Frequent Miler on the air discussion!! I think the best way to determine which miles to go after in promotional card bonuses is to read your articles on “how to get the most from Delta miles, ultimate points, AA, Virgin Atlantic… etc.. that your true value to me.. i like the idea of international business points valuation since you can fly pretty inexpensive in the US on Southwest, Jetblue and other low cost carriers. So you understand where I come from, which then may make my response void for most (retired, single player, travel for fun, no referral bonus opportunities).. but I do get so much value out of your information!!

Great consideration of a complex subject — modeling the “true” value of airline miles.

When you start developing a data-based model for business class flights I think you’re going to run into some issues that will complicate things further:

Which is all to say — good luck with a complex task!

Good points!